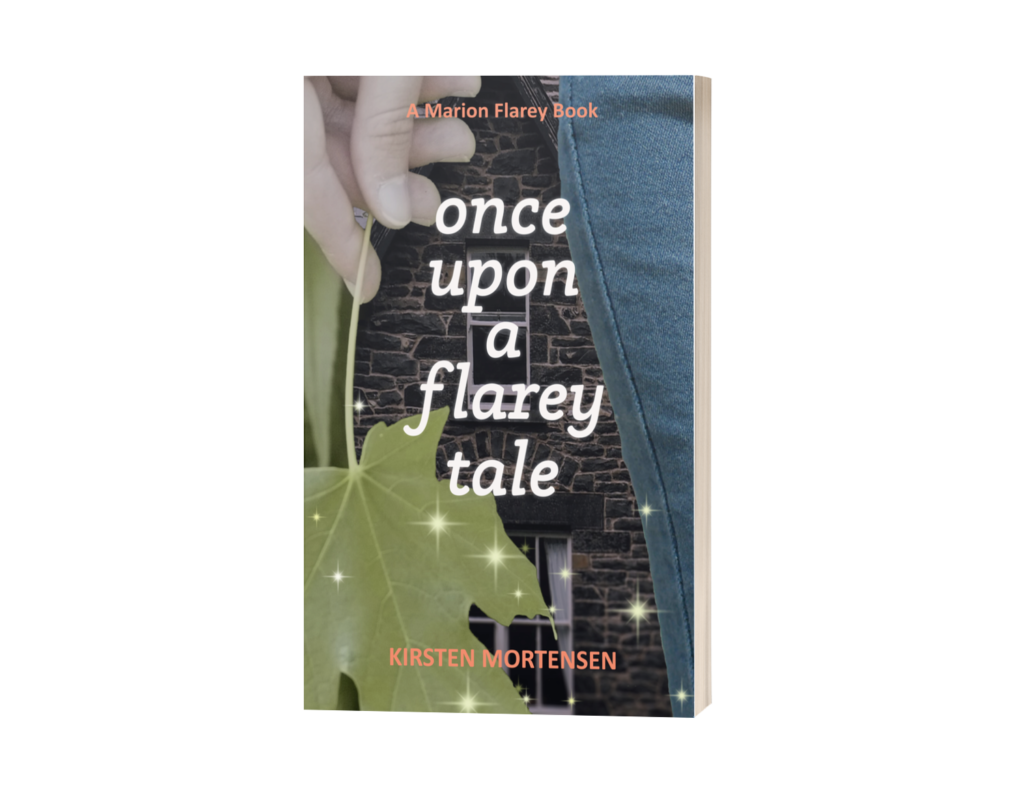

How about this? Once Upon a Flarey Tale won a first place Incipere award for Women’s Fiction – Clean :) :) :)

I am STOKED.

I am seriously honored and seriously STOKED!

How about this? Once Upon a Flarey Tale won a first place Incipere award for Women’s Fiction – Clean :) :) :)

I am STOKED.

I am seriously honored and seriously STOKED!

I came across this tweet around the time Kirn (substack here) posted it, and it continues to haunt me.

I don’t know how many physical books I have collected. Five or six hundred, perhaps. It seems, to me, to be “not a lot,” so it shocked me just now when I quickly estimated the count.

If they were shelved compactly in one place, they might cover one wall or so of a smallish room. And yet. They take up space and gather dust. And every time I move (I have moved, on average, every 3.5 years since I graduated college — does it ever end, this moving?) they are such a troublesome thing to pack and unpack and sort and re-shelve.

So when my sweet father, who read books constantly, gave me a Kindle (I’d begged him not to, but he loved his so much, and so much liked to share that kind of thing with his family) I thought, okay, now I’ll be able to read on without piling up more and more physical books. This is good, I thought. “I’m comfortable that certain experiences are supposed to be ephemeral,” I blogged. “I’m okay with some books as experiences rather than things.”

But then came the stories about Amazon erasing peoples’ books from their Kindles (some sort of issue with copyright or publisher disputes, the story would go) and I became a bit uneasy.

When you buy a “book” for an e-reader, you don’t really own the book, as it turns out. You have paid for permission to read something that belongs to someone else. And “they” can take back that permission any time they please. (And my father’s Kindle? The books on my father’s Kindle? I took photos of the screen — screens, pages of them — so that I would know what books he “owned.” They are gone, now that he’s passed and no longer “pays” for his “account.” There’s your “ephemeral.”)

I have also had a longtime habit of picking up used books that struck me as unusual, or that I learned would be going out of print. I bought an old edition of The Joy of Cooking when I learned that new editions have dropped the recipes for cooking game. I read at some point years ago that Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations was being revised — modernized — so I hunted down a second-hand copy (the centennial edition published in 1955). (I adore that book. It may be my take-on-a-desert-island-game book.)

I’m old enough to have lived through the transition as second-hand booksellers began selling online. It drove up the price of old books — that copy of Lyrics of a Lowly Life by Paul Laurence Dunbar that I picked up for 50 cents in a junk store in my home town in the early ’80s would be displayed in a locked case, today, and likely priced at $100 or more. (Of course you can buy reprints of it for pennies — have you ever bought a book, thinking it was second-hand, only to find out it was a cheaply made reproduction? The quality so poor it was basically unreadable? I have. I will not, ever again, if I can help it.)

And I remember as well reading — also years ago — that decorators were buying up antique hardcover books — the ones with ornately decorated covers and gilt-edges pages — and using them as, well, decorations. In some cases they were gutting the books and using just the covers. Because what mattered wasn’t the words inside but the effect walls of books would convey, the image they’d convey of erudition.

It was around this time that I became weary of being outraged. Is that cynicism?

Not to say that I’m no longer outraged, ever. I am, believe me.

But — and this is more pronounced now than ever, since I lost both of my parents (within a span of less than a year), my birth family now basically as gutted as a home decorator’s empty books, not to mention these godawful exhausting never-ending lockdowns — I am, more and more, handling my outrage by becoming quiet, by turning inward. I am thinking — all the time, basically — about soul, and about words, and about preservation. Not preservation of myself but of what really matters — what will always matter.

Thinking about whether the outward things I preserve, the words I preserve, could ever help someone else, one day, grope a bit closer to some faint Light.

That I shouldn’t gamble with such a thing.

It’s been several years, now, since I began to regard my Kindle as a device, solely, for what I consider to be throwaway books — I know that sounds pejorative but what I mean is books I would under any circumstances read only once and then pass along (and the Kindle is also very good for reading samples for free).

I’ve started to buy up physical copies of the books on my Kindle that I do not consider one-time reads.

Which leads, of course, into the next phase of my weird relationship with Amazon. (Seems it’s always about Amazon, isn’t it?) Now with their new policies, their decision to start taking books off their platform — once again reminding me as it does all writers of our uneasy truce with That Company: I am utterly dependent on Amazon if I’m ever to sell my novels in any numbers whatever; “my” readers are not really “mine,” they are Amazon’s “customers,” no matter how ridiculous and unfair that may be (and before you defend them — because yes, I know they do me a service by building their platform and attracting traffic and letting me sell my books there — when I have, in the past, bought other things from them, cosmetics or whatever, I have gotten emails from the seller, I have gotten direct mail, snail male from the seller. How can other vendors “own” customers that came to them via Amazon but writers cannot? There is no happy answer to this, I suppose. I suppose these other sellers have done their own fulfillment. I suppose there are so many writers that we are, to Amazon, something of an unwashed hoard, with a handful of exceptions more trouble than we’re worth.)

In any event, I’ve been going to Alibris instead of Amazon more and more. Telling myself maybe that helps, in some small way, other booksellers (“hello?” “echo echo echo…”). And I am picking up more and more second-hand copies of old books. Despite the fact that my shelves are full and we’ll likely be moving again sometime in the not-too-distant future and once again I’ll be packing books in boxes…

And I am increasingly aware of how I feel, when I sit near my shelves of books, thinking or journaling or writing, and I need to look something up and I scan my titles and find a book and page through it. Like right now, for example. Marshall McLuhan, The Global Village (I own the Oxford University Press 1989 edition):

All media are a reconstruction, a model of some biologic capability speeded up beyond the human ability to perform: the wheel is an extension of the foot, the book is an extension of the eye, clothing an extension of the skin, and electronic circuitry is an extension of the central nervous system…

My books — I feel this as I sit near them, scan their titles — are also an extension of my mind, of my memory. I very often go back to books I read decades ago (I haven’t opened the McLuhan in probably 20 years) with that same felt sense that arises when we go back into our mind’s memory banks to pull something out that we once experienced and would like to look at it again and draw upon, again, because it will add some sort of richness or meaning to what is happening now, today.

So if I look for a title and can’t find it right away (I don’t have enough space on my shelves; about half of my books are stacked behind the other half; my books hide on me, sometimes) I become anxious, even, at times, agitated. It’s like I’ve lost a bit of what should be there, should be recallable. (I was looking the other day, for my copy of The Great Gatsby and can’t find it and it still bothers me…did I lend it to someone? Should I buy another copy? Would I be able to find the same edition I owned?)

Ephemeral, indeed.

Sigh.

Buy physical books now. Great ones, good ones, bad ones, ones you happen to like. Store them safely as you would treasures. They are. Some will become unavailable soon, I suspect, for reasons that may not be stated candidly. If I’m wrong, what have you lost?

We, the library.

—Walter Kirn

Books as an extension of mind — an extension of our thoughts and memories. Individually and collectively.

“We, the library.”

What happens to our books, if we, their contemporary guardians, decide to begin culling them?

And if we cull them, what injury are we committing that we cannot feel (the brain can’t feel pain, right?) but that will one day exact an awful price — one day we’ll wake up and sense a gaping hole where, we know, some memory ought to be?

I am buying more books, now, than I’ve bought since I was in college. Unapologetically. Knowing that it means I have more “stuff” that I will need to cart around, that someone will one day have to dispose us when I am dead.

Unapologetically.

So I learned about Physics of the Stoics via a wikipedia footnote and hunted down a copy because the protagonist of one of the novels I’m writing (Scratch) is a Stoic, in the formal sense.

And as I read about Stoicism (sticking to translations of ancient texts, since my protag isn’t a herd guy; he consults the originals, not the burgeoning pile of Stoic pop-lit) I became curious about what the ancient Greek stoics meant when they talked about “nature.”

Example, from Marcus Aurelius, Meditations.

Don’t ever forget these things: The nature of the world. My nature. How I relate to the world. What proportion of it I make up. That you are a part of nature, and no one can prevent you from speaking and acting in harmony with it, always.

What, I wondered, would Aurelius have meant when he thought about “nature”?

Physics of the Stoics helped me get a bit closer to imagining an answer (whether it’s the right answer or not, who knows. hahahaha.)

For the ancient Stoics, reality was permeated by pneuma, which they in some cases defined (as translated) as a substance consisting of “air” and “fire.”

What I try to do as I consider these concepts, however, is to achieve a kind of mental elasticity.

As a modern human, I was taught that pre-modern scientific models were nonsense. The world is made of whirling electrons, not a mix of air, fire, water, and earth.

But perhaps that dismissal is a bit too pat and a bit too arrogant.

Full disclosure: Per a review of Bernardo Kastrup’s Meaning in Absurdity that I recently posted on Goodreads, I’m a philosophical idealist. Ergo I believe that reality is actually consciousness, not matter.

Therefore, I believe that the models we use to examine reality and explain it phenomenologically are just that: models. Insofar as they seem real, it’s because we are interacting with reality and our interaction collapses possibility into the seemingly-objective.

So in considering how the ancient Greeks understood the world, perhaps their model was as valid as anything we’ve dreamed up.

I mean “valid” quite literally. In “Meaning,” Kastrup discusses the work of Thomas Kuhn, a 20th century philosopher of science, who proposed that objective data “cannot be gathered and interpreted outside the context of a paradigm,” defined by Kastrup as the “basic assumptions, values, and beliefs held by scientists about how nature is put together.” Continues Kastrup:

…we cannot know for certain that the laws of physics are the same throughout space and across time…paradigms change over time, and along with them what science considers to be true or reasonable.

Kastrup is careful to add a strong caveat that this is not an argument for relativism. But for the purposes of my Ancient Stoics thought experiment, insofar as they developed a model that made complete sense and actually explained the world, absolutely it was “valid.”

So, to play along: pretend you were never taught anything about modern physics, but understood the world strictly on the basis of your own senses and mind.

Air is, essentially, nothingness: it’s undetectable by our senses. Yes, we can detect its movement but not air per se.

Warm air is nothingness with a quality associated with life (warmth) (movement is another quality that is associated with life, and fire is both warm and in constant motion).

So why not propose a model of reality where everything is permeated by “air” (a nothingness that is also a something); and where “nothingness” merges with other qualities to generate phenomena such as objects and living beings?

In addition to qualities like warmth and movement, other subjective qualities such as rationality are also self-evidently aspects of that nothingness; after all, they have to arise from something, right?

That is pneuma. It is cohesive; it is everywhere; it must be what holds everything together. It is the “field” from which everything else arises. It’s the logos of the Gospel of John: there from the beginning, that through which all things are made: the light of man, the Christ consciousness.

To be clear, I’m not rejecting modern physics. That would be stupid; it’s very useful and I am eternally grateful to have been born today instead of 2500 years ago. But as a way of penetrating the nature of reality by seeing it through fresh eyes? This book was a lot of fun :)

Note: links in this post are affiliate links. If you click one and buy, I get a small percentage. It doesn’t add anything to the price.

I love Romance.

I write Romance.

Not in the sense of genre romance, but Romance in the sense of an affirmation of the centrality of the heart in human experience. Of the perils of our alienation from nature, and because Romance gives us a break from the sheer awfulness of life (Byron: “And if I laugh at any mortal thing, Tis that I may not weep.”)

My question is: can novels help people learn better (learn again?) how to think?

Yes, reading novels is a form of escapism.

But can they draw people into stories and then use those stories to train people, not what to think (blech) but how?

I hope so.

I’m so horrified by how poorly people think …

Out now! Book 2 of my Marion Flarey series :)

Available on Amazon for Kindle or Print, or click here to browse other e-formats.

Those of you who know me personally know that this past year has been incredibly difficult. Yeah, I know I’m not alone. COVID etc. But in addition to the social upheaval, my personal life was turned upside down as well. First, my dad passed in April. And now my mom is gone, too. January 9.

I am not even sure how to process it, to be honest. Looking forward to when this is all something that happened instead of something that is still happening.

In the meantime, I have been getting some writing done, although work has been a bit slower than I would have liked.

Once Upon a Flarey Tale came out last August.

Now the second book in the series, Fo Fum Flarey, is available.

Here’s the description of Fo Fum Flarey:

A tale about love, life choices — and how trusting the wisdom of old stories is sometimes the best choice of all.

Marion Flarey has finally found him. Fletcher Beal.

Her Prince.

And when you find your rich, handsome Prince, everything is settled, right? The fairy tales say so! You live happily ever after. No more questions, no more stress.

But as much as Marion loves those wise old tales, there’s a limit to their magic. How is she supposed to make her place in her new prince’s world — especially when Fletcher is always busy, flying around the country, exploring new domains and adding conquests to his kingdom?

The stories don’t say.

To make matters worse, her family is gripped by stories of their own — and Marion can’t figure out what’s going on. Her mother is distracted and unhappy. What secrets is she hiding? And then Marion’s brother, Ace, shows up in town — and Marion learns why he left.

He’s a thief.

He stole from their family.

Worse yet? He stole from Marion’s prince.

Can Marion unravel her family’s secrets?

Can she rescue her brother?

Can she put her broken family back together again?

And should she even try?

Or will her family’s crazy problems sabotage Marion’s life, robbing her of the one thing she wants most: a happy future with her sweet, rich, sexy prince?

As some of you know, one of the novels I’ve been working on for some time, now, is a retelling of Goethe’s Faust.

The translation I purchased when I first got the idea for the novel is the Norton Critical Edition, translated by Walter Arndt. (And if you would like a copy, shoot me a note, because I own two and would gladly give one away.) (Why do I own two, you ask? Because last time I moved, I couldn’t put my hands on my copy and bought another, and of course precisely one nanosecond after copy #2 arrived in the mail, I spotted copy #1 on my shelf, because nothing on this planet makes sense. But I digress.)

With regard to my novel, first let’s get one thing out of the way. I am in no way up to the task of retelling Goethe’s Faust. It’s ridiculous for me to even type the words. I should be ashamed of myself for even thinking the words.

But nothing on this planet makes sense. So: onward.

As I planned the novel — the title is Scratch, in case you’re wondering — I read and re-read my edition of Faust.

Have you ever read it? The whole thing?

It is … not an easy piece of literature.

I knew Act 1 from college. Somewhere, along the line, some professor assigned it and I read it.

You probably know the storyline as well. The devil (Mephistopheles) makes a bet with God that he can trick Faust into surrendering his soul. He then appears to Faust and strikes a deal with him: if he can deliver a certain type of experience to Faust, he can have Faust’s soul.

The experience Mephisto promises is one of total fulfillment. He’ll set things up so that Faust finds something happening to him so marvelous and engaging that he never wants it to end. And if Mephisto can do that, the devil wins his bet.

Faust agrees to the terms.

Mephisto spends the rest of Act 1 trundling out the usual experiences. He makes Faust young again, and rich. Faust falls in love with Gretchen, a sweet young virgin, and Mephisto arranges for them to become lovers, thinking that will be Faust’s ultimate experience. It doesn’t work. Sex with Gretchen is nice but doesn’t quell Faust’s hunger to keep striving for Something Else, Something More. Gretchen’s life, however, is utterly ruined. She becomes pregnant and, in her shame at being an unwed mother, kills her child and is sentenced to death herself. She dies in prison before the execution is performed.

This portion of the play is fairly easy to follow. Pact with the devil, ruined woman, isn’t it awful that out-of-wedlock pregnancy was once considered to be so sinful that it would drive women to commit atrocities.

The next four Acts, on the other hand, are complex and often surreal. They are laden with allegorical characters and events that in some cases are comments on contemporaneous European and German politics, on the tension between Romanticism and Classicism, on fiscal policy, on urbanization. The settings are at times “reality” but at times fantastical places — imaginary realms.

And then comes the final bit, where Faust dies. He’s in the process, during this last act, of reclaiming land from the sea and using it to build out a planned community — an urban utopia. He is also struck blind by Care, an event that is associated in the drama with Faust’s cold-hearted theft of land from an elderly couple (Faust wants the land as part of his urban development project; he asks Mephisto to get it for him; Mephisto murders the couple).

Because he’s blind, Faust doesn’t realize that the digging he hears at the end of the play isn’t workers, laboring at his urbanization project. It is demons, digging Faust’s grave.

Faust proclaims he’s so pleased with the idea that people will benefit forever from his reclamation project and the community he’s designing, that he would gladly tarry in that moment forever. He falls over and dies.

Bingo. The devil wins, right?

Not so fast. Angels intervene, distract Mephistopheles, crowd him away from Faust’s body, take possession of Faust’s soul, and whisk him away to heaven.

And ever since, people have been arguing about those last few plot twists. What, exactly, was Goethe trying to say?

On the face of it, it seems like Mephisto won the bet, and then heaven essentially cheated. Pulled a fast one. He certainly believed he was cheated. “Where do I sue now as complainer? … This thing was wretchedly mishandled.”

Or maybe not. Maybe the devil didn’t win the bet. Mephisto himself says, right after Faust dies:

So it is over! How to read this clause?

All over is as good as never was,

And yet it whirls about as if it were.

The Eternal-Empty is what I prefer.

If all, in the end, is nothing, then Faust’s proclamation that he would tarry forever in the feeling of building his new community is also “nothing.” So did Mephisto, in making this statement, essentially void his own bet?

Another observation. Blind Faust may have thought he was experiencing the building of his community. But he was not. He was experiencing the digging of his own grave.

It was a trick. So was the bet won not fairly but by cheating? And did that negate it?

The Prince of Lies cannot resist lying. It is his nature. Did he undo his own success by founding it on a lie?

Another possibility is something along the lines of theological determinism. Heaven and its beings are outside of time and space and are not, therefore, subject to the same laws as we humans are; outcomes of our actions are pre-determined. Any wager made on Earthy may seem valid to us, but its terms can’t necessarily be applied in heaven, because in heaven, redemption and damnation are decided on completely different terms. Whether we are to be redeemed or not has already been decided, and can’t be changed just because we cut a bad deal with the devil while we’re incarnate.

Redemption, from our perspective, is therefore inexplicable, irrational, and probably undeserved. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen.

Faust is a metaphysical work. Its roots are in Medieval morality plays, which are as straightforward as a child’s story. The devil is evil. To do evil is to enter into a pact with the devil, and the price you will pay is your eternal soul.

But in Goethe’s world, things aren’t so straightforward. His Faust is no saint, but is beloved by God for all his shortcomings (“Though now he serves me but in clouded ways,” God says in the play’s prologue, “Soon I shall guide him so his spirit clears … Man ever errs the while he strives.”)

Perhaps, in Goethe’s drama, the omniscient God is unworried about his wager with the devil because He knows from the beginning that Mephisto will fail, partly because of the devil’s own nature, but perhaps also because of the nature of redemption itself.

And so, Faust was mistaken when he thought that what he heard, in his last day on Earth, was loyal laborers, busily working on his project. “Man ever errs the while he strives.” Add to that intercession — Gretchen, in heaven, prays for Faust — and you have everything you need to overrule Mephisto’s trickery. As the angels say while they’re carrying Faust’s immortal essence up to the highest heavens:

Pure spirits’ peer, from evil coil

He was vouchsafed exemption;

“Whoever strives in ceaseless toil,

Him we may grant redemption.”

And when on high, transfigured love

Has added intercession,

The blest will throng to him above

With welcoming compassion.

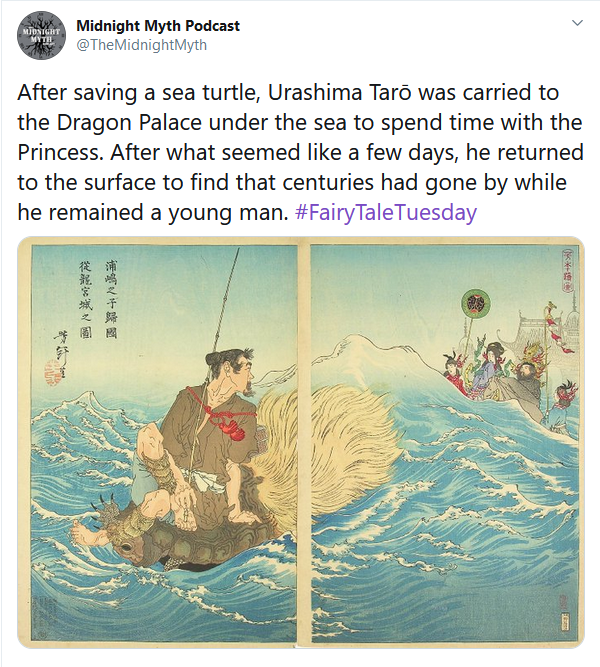

On Twitter, Midnight Myth Podcast (podcast can be found here) shared a Japanese story for yesterday’s #Fairytaletuesday.

I was struck by the beauty of the illustration, of course, but also by the fact that missing time crops up in so many folklore traditions, across so many cultures.

But wait! There’s more.

What if stories like this one are more than “just stories”?

You may be aware, for instance, that missing time crops up outside of folklore. People literally experience missing time when they stumble into certain kinds of paranormal phenomena — they have subjective experiences of time that don’t match up to the linear passage of time in “the real world.” Missing time is an almost universal aspect of UFO abductions, for example.

After a ferocious mental struggle, during which she literally tried to crawl out of the house as she could no longer walk, all went dark. When she woke up, it was hours later. She never found out what happened to her during that missing time.

— The Super Natural: Why the Unexplained is Real, Whitley Strieber and Jeffrey J. Kripal

Which brings me to a question I’ve been tussling with for over a year now, as I build out my Marion Flarey books — a three-novel collection that will debut when I publish Once Upon a Flarey Tale in a month or so. [UPDATE: it’s out and you can get your copy here!]

What if they are actually templates that — in the right hands — can be used to harness and direct emotional and spiritual energy in ways that shape reality itself?

Marion Flarey seems to think so. She detects a power in fairy tales that nobody else seems to “get” (well — almost nobody!) — but that also tends to blow up in her face when she tries to wield it. :)

And here’s where — to me at least — it gets interesting.

I think she’s right.

Or put another ways: these books are fiction, but they are also true. I am not writing “paranormal.” I’m writing reality — or let’s call it quantum reality :D

Here’s what I mean, using the missing time template as an example.

If you study the template, you can feel the energy behind it. Quite a lot of energy, some negative (anxiety) and some positive (time pressure can be a powerful motivator).

In some stories, like the one Midnight Podcast shared, the energy is partly sexual. It’s about the power of sexual love-matches to make us completely forget — completely abandon — other loyalties and ties.

The handsome they like, and the good dancers. And if they get a boy amongst them, the first to touch him, he belongs to her.

— Mr. Saggarton, as told to Lady Gregory, Visions and Beliefs v. 1

The missing time template also warns us to be conscious about the trade-offs we make when we decide to take a particular life-path.

You can’t take two paths at the same time. Once you have invested time exploring one path, you can never get that time back. It’s gone forever.

She hastened homewards, wondering however, as she went, to see that the leaves, which were yesterday so fresh and green, were now falling dry and yellow around her. The cottage too seemed changed, and, when she went in, there sat her father looking some years older than when she saw him last; and her mother, whom she hardly knew, was by his side …

— The Elfin Grove, from The Big Book of Stories from Grimm, ed. by Herbert Strang

There’s a profound emotional poignancy, here. When we leave our birth homes, those we loved when we were children will, in our absence, grow and age and eventually die. And we’ll miss that, because we were elsewhere — we were Away.

Because of the poignancy of this trade-off, missing time is also related to death, naturally (what isn’t?): whether we permit ourselves to be aware of it consciously or not, we are all on some level keenly aware that our time on this planet is finite. Sooner or later, Mr. Death is going to knock on the door and whatever we are working on at that moment will remain forever unfinished.

It’s scary, right? Because life isn’t fair and and the trade-offs we make, when we decide how to spend our time, are often downright cruel.

But there is one small comfort in this rather ugly mess: we have the ability to consciously shape our personal stories — the stories that, in turn, become the channels through which our lives flow.

In other words, we don’t have to be carried passively toward the inevitable penalties of Lost Time. We can recognize those penalties in advance; we can accept them with open eyes as the price we pay for a choice we consciously make.

Will this make those penalties less painful?

Rip’s heart died away, at hearing of these sad changes in his home and friends, and finding himself thus alone in the world. Every answer puzzled him too, by treating of such enormous lapses of time, and of matters which he could not understand: war—Congress–Stony–Point;—he had no courage to ask after any more friends, but cried out in despair, “Does nobody here know Rip Van Winkle?”

— Rip Van Winkle, Washington Irving

Nope. Still gonna hurt.

But it will make the experience of suffering those penalties one of conscious choice. We can therefore consciously acknowledge the richness of life’s tapestry, which is woven not only of beauty and joy and pleasure, but also of ugliness and loss and pain. And that’s something. It’s quite a lot, in fact …

This is what Marion is trying to do.

It’s hard for her, just like it’s hard for us.

It’s also absurd, and confusing, and funny, and has a tendency to backfire :)

But ultimately it’s as rewarding for Marion as it can be for you and I.

Because the better we get at shaping our stories consciously, the more aligned we become with our own sense of place, and our own sense of destiny.

And what could be a better HEA than that?

“Once Upon a Flarey Tale” is available on Amazon for print or Kindle, or click here to browse other e-formats.

UPDATE: the day I posted this, my dad was admitted into the ICU with covid. So I failed my resolution utterly …

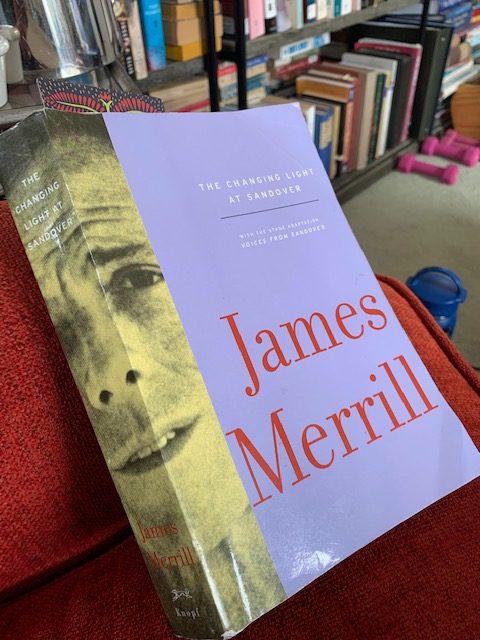

Okay so it’s National Poetry Month, and also national stay-at-home month, so I’ve decided to read a book of poetry that I bought last summer but set aside.

The Changing Light at Sandover. James Merrill. Also, it’s over 600 pages. So 20 pages a day and it’s already April 2 and I have some catching up to do.

If you haven’t heard of this poem, here’s a NYT article from 2008, which notes that the poem is based on Merrill and his longtime partners’

adventures with the Ouija board, with which they summoned from the dead, among others, W. H. Auden, Plato and a peacock named Mirabell.

And from The New Yorker:

And Ouija boards: Merrill made the most ambitious American poem of the past fifty years, seventeen thousand lines long, in consultation with one. The result, “The Changing Light at Sandover,” was a homemade cosmology as dense as Blake’s, which Merrill shared with the “summer people”—retired naval officers and frisky elderly Brahmin ladies—who lived near him in Stonington. He knew that posterity alone would decide on his greatness; he would not be around to enjoy the proceeds. He hedged his bets by driving a small Ford with a license plate that read “POET.”

Will I finish the book? I don’t know. But being locked up and I can write my own stuff for only so many hours a day, and it feels like this April may be not only the cruelest month but also the longest …

The cup twitched in its sleep. “Is someone there?”

We whispered, fingers light on Willowware,

When the thing moved. Our breathing stopped …

“And there’s many would tell you that every time you see a tree shaking there’s a ghost in it.”

Lady Gregory, Visions and Beliefs

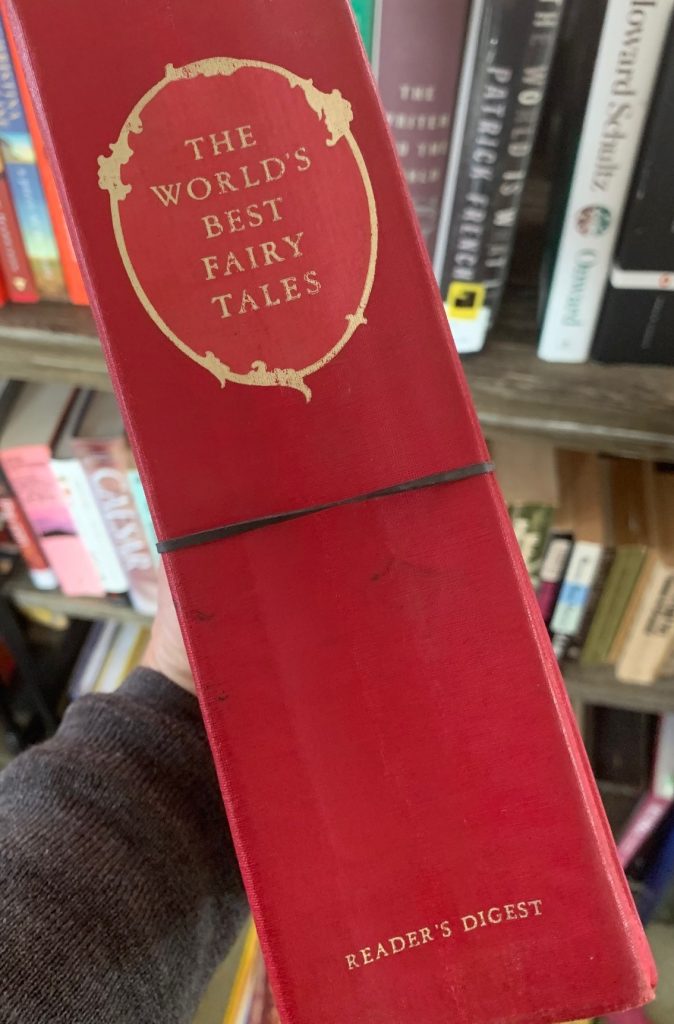

Okay, so I don’t often do product endorsements on this blog.

But I love books.

I own old books.

Old books break.

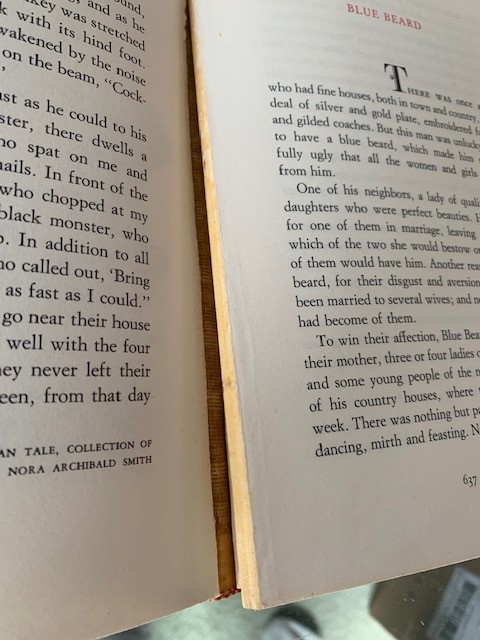

Like this book. It’s The World’s Best Fairy Tales, a Reader’s Digest book my grandparents gave me in 1968. And OMG how I loved this book! I must have read every story in it a million times. (I also used to make Grandma read to me out of it — makes me laugh now thinking of it — I wonder if she ever regretted gifting it, maybe? A teensy bit? Because of course I used to request the longest story in the book, Sinbad the Sailor. I think it’s 50 or 75 pages :D)

Anyway, today I pulled the book out and GAH.

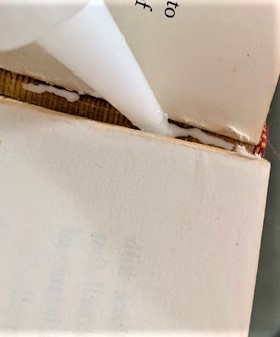

The original glue had become completely dry and brittle. I no sooner touched the thing and chunks of pages started to fall out.

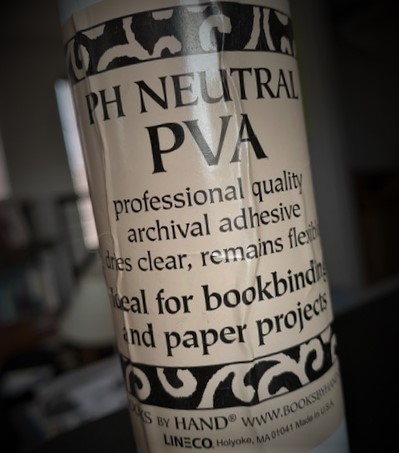

Fortunately, I have a fix. This stuff –>

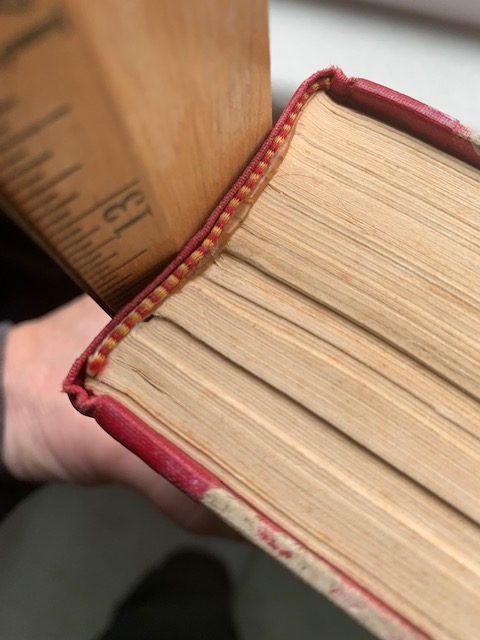

Its an adhesive that is flexible when it dries. So when you open the book the spine can flex like it’s supposed to.

Step 1, open the book to the spot where the pages are starting to fall out.

I try to be super careful while I’m doing this so that I don’t break the book even more. Because the last thing I want to have to do is glue the pages back in one at a time =o

But usually what happens is what you see here: chunks of pages falling out …

Step 2: Run a little bead of the adhesive down the inside of the spine.

I try to be careful here, too. I figure, too much adhesive and it might leak into the pages.

The trick is to move the tip of the bottle kind of swiftly and smoothly so that the bed is thin and light.

First time? Practice first! Lay a bead down on a piece of paper, before you start on the book, so that you get a feel for how fast you should go to keep the line of adhesive thin & light.

Step 3: Press the pages back into place.

So far, every time I’ve done this, I’ve been dealing with chunks of pages. So it’s kind of easy to just press and tap the pages as a chunk.

Step 4: Check to make sure the pages are nice and flush. You want to make sure that the adhesive is adhering to both the spine and the pages :)

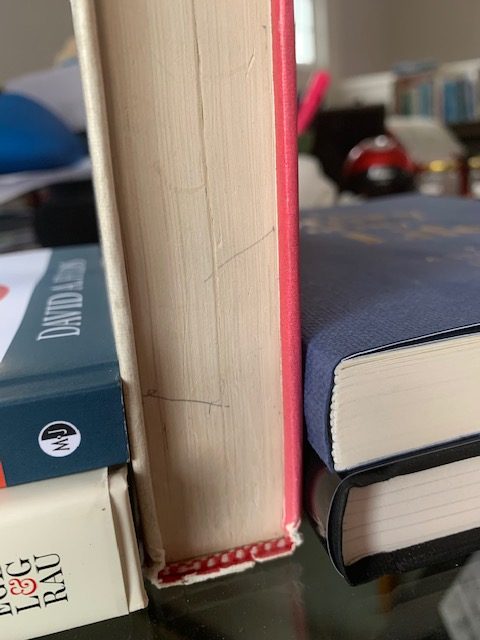

Step 5: Rig something to keep the pages flush against the spine while the adhesive dries.

For some of the books I’ve fixed this way, I’ve just set the book on a table, spine down (propped by other books to keep it from tipping over while the adhesive dries). When I fixed my old Roget’s Thesaurus, that’s what I did. The weight of the book was enough to keep the pages pressed against the spin until the glue was dry.

But for my Fairy Tale book, I got a little creative. It’s a thick book — 2 and 1/2 inches! — so the spine tends to curve inward slightly.

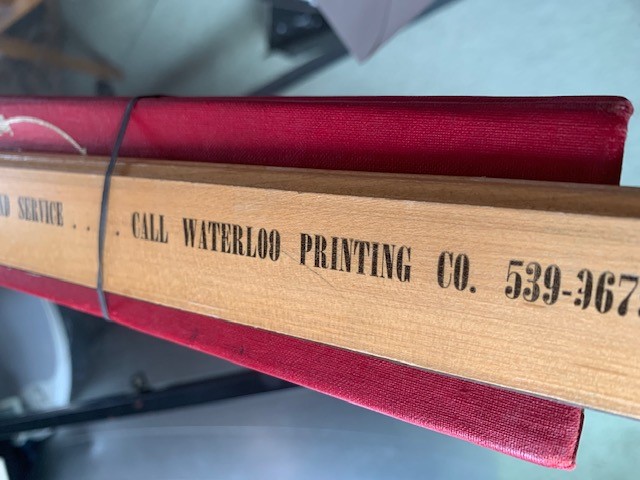

So I used a rubber band to strap a wooden ruler against the spine.

It just happened that one side of my ruler is kind of convex, so it worked perfectly. It snugged right up against the spine.

Step 6. Wait for a day or so until the adhesive dries. And that’s it!

Would I try this on a valuable book? Probably not. I’d probably take that sort of book to a professional to be restored. (And yeah, I see that in some cases people are asking for a lot of money for World’s Best Fairy Tales. But you can also find copies for cheap. So yes, I recommend you pick up a copy if you’re a fan, but maybe don’t spend $80 for it.)

But for old books that I just want to be able to handle again, this stuff is fabulous. I’ve fixed the dictionary I’ve had since I was a kid, I’ve fixed this old Roget’s thesaurus that I absolutely adore (sooo much better than online thesauruses. Really.)

And now I’m fixing my beloved Fairy Tale collection :)

Did it work?

Did you use PVA?

Drop me a note or leave a comment!

P.S. this post includes affiliate links. If you click and buy I get a few pennies — no extra cost to you. But I promise you, you will be soooo glad you have a bottle of this stuff on hand. Thank you!