This is a peculiar book, in some ways. I loved it. But I am weird.

I picked it up because I’ve turned back to a novel I’m writing (Scratch) that is a retelling of Goethe’s Faust.*

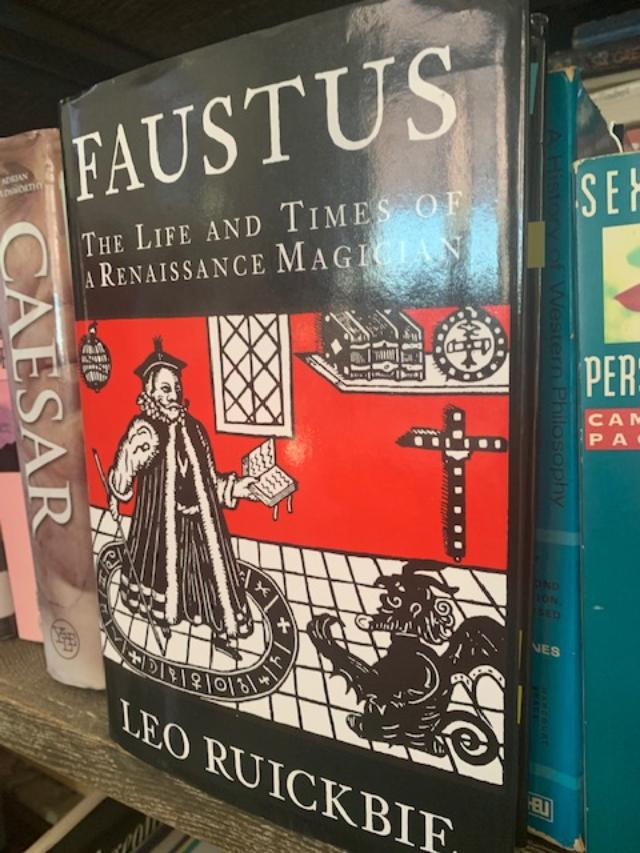

And as I’ve chipped away at Scratch over the past several years, I’ve read the Goethe a couple times, of course, and Marlowe, and I’ve poked around the Interwebs. And then I found this book by Ruickbie, and bought it, and stuck it on my shelf (my real shelf, not my Goodreads shelf, there’s only so many hours in the day).

And then a month or so ago I started to read it. And I loved every page.

Start with a historical figure, Doctor Faustus, who is with us, today, almost entirely as a myth. He existed. He was a flesh and blood man. But there is scarcely any record of the historical Faust. There are scattered mentions in letters and such, but they are typically little more than a sentence or two. There are published accounts of Faust’s life and deeds, but they appeared decades or centuries after his death; they were typically passed off as authentic, but upon close examination can be confidently dismissed as fabrications. We aren’t even sure what the guy’s real name was.

Enter Ruickbie, who is a historian. And he sets out to write a historical biography of this historical figure, Doctor Faustus. He digs into the correspondence of Faust contemporaries, he digs into legal documents. And he chases down a bunch of “local traditions” that Faust was involved in such-and-such shenanigans in such-and-such a town or inn or house, but when he looks into them, almost all of them appear to have no basis in historical fact.

So now what?

Ruickbie does something that I think is pretty cool: he builds a historical account around what is often an educated guess about where Faust was, what he was up to, and how his contemporaries were reacting (or in some cases would have reacted) to him.

So you don’t really get Faust, with this book (I told you it is peculiar!). What you get is tantalizing wisps of Faust — and then, what you really get is Faust’s milieu. And it’s very granular and vivid, because Ruickbie knows his stuff and has put in the time to build it out in a very granular but vivid way.

And it was a crazy time, the late 1400s, early 1500s.

And yes, I love history, but I haven’t been exposed to a ton of European history from that time period, so for me it was a delight. I didn’t know, before I read this book, about the Peasant’s War (spoiler: the peasants lost). I didn’t know that in 1524 there was a conjunction of seven planets in Pisces (my sign!) and the astrologers of the time predicted massive floods (water sign!) and people panicked. Widespread panic. Half of the population of London at the time fled the city, convinced that if they didn’t the Thames was going to rise up and drown them. I didn’t know that in 1532, Anabaptists took over the fortified German town, Munster, and were besieged and then Munster fell and the Anabaptist prophets were captured and tortured, yick.

I love history. I love how everything is different and yet everything is the same. It makes my head spin — in a good way, like when you look up at the stars and realize how big space really is.

Ruickbie is a good writer. It’s hard to write history because history is about people and personalities; to write history, you have to introduce the reader to piles of strangers; if you don’t make them come alive, your reader won’t be able to keep track of them, and the history dissolves into a mash of meaningless and forgettable faces.

But Ruickbie pulls it off. I suppose it is because, in the end, he has a point of view about everything that was going on, during Faust’s life–about Faust, his contemporaries, the religious and political leaders who were alive at the time. So Ruickbie isn’t reciting dates and names. He’s pulling the covers back, revealing what all those people were probably like, what probably motivated them to do the things they did. A big example, and pivotal to Ruickbies point of view: did the historical Doctor Faustus really make a deal with the Devil? Or was that a slanderous fiction promulgated by Faust’s contemporaries who, it turns out, were probably competing amongst themselves for lucrative gigs doing astrology and such for kings and princelings?

And if it was a slanderous fiction, where does that leave us? For Ruickbie, the real story is about the religious tensions of the day. Faust lived at a time when the Renaissance was giving way to the Reformation. Faust, like every other person alive at the time, was caught in the current of history. As are we, today.

Highly recommend this book for anyone who enjoys history.

*Sidebar: as I’ve mentioned that’s not to say I have the chops to pull off a retelling of Goethe’s Faust. I’m sure I am not up to it. But it so happens that after this awful year, losing both parents blah blah blah I needed to take a break from the lighter romancy stuff I usually write and do something that, to me at least, passes for Art. So I set aside the Marion Flarey project for now and went back to Scratch for a bit.