If there is one thing I’ve learned about trying to “be” a novelist — more accurately, trying to pursue a career as a novelist — it’s that you get knocked on your ass. A lot. Over, and over, and over…

And since I follow a few writers on Twitter, I see a fair number of who are crumpling. In real time.

I can relate. I’ve been there more times than I can count.

The lessons this business teaches are hard lessons, and the tools it uses to teach those lessons can be brutal.

Been There, Done That

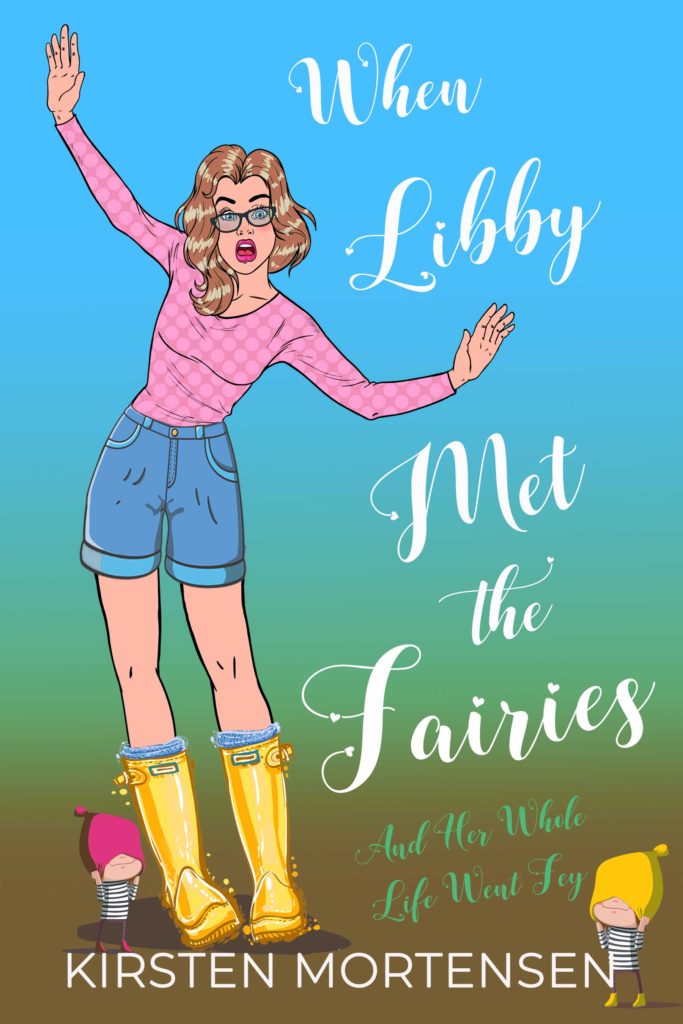

One of the worst lessons I’ve had to endure started shortly after I published one of my first novels, When Libby Met the Fairies.

It was 2012. Self-pubbing was still pretty new.

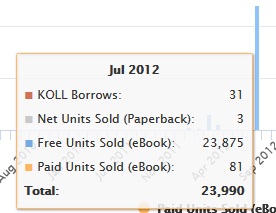

I ran a KDP giveaway. A successful giveaway! A 23,875-people-just-downloaded-my-book giveaway! And I thought I’d made it. I thought that, with that many people reading one of my novels, my future was a gleaming bright golden road with golden coins showering down around my ears from endless sparkling rainbows.

From the days when running a KDP giveaway was so easy, a total newb could do it…

Boy, was I wrong.

Readers hated the book.

Okay, not all of them. And maybe “hate” is too strong a word. But in those days, Amazon used reviews in its ranking algorithms (although I’m told that’s no longer the case now) and I got slapped with enough 1- and 2-star reviews to kill the novel — and with it, my dreams of eeking out anything like a living self-pubbing novels.

At least in the near-term.

I tried to be brave, but in the end, I crumpled. I cried. I (stupidly) tried to argue with the critics on this blog (post since deleted).

And, eventually, I just gave up and unpubbed the book. It wasn’t selling anyway, and those reviews hurt. Better to pretend the novel had never existed …

But this post is about lessons, not mistakes.

Specifically, it’s about a lesson that was once so painful to my ears that I refused to believe it could be true.

I don’t remember where I read it. Probably on one of the lit agent blogs that were all the rage back in the early 2000-teens. It went something like this.

Write your first novel. Set it aside. Write your second novel. Set it aside. Then go back to your first novel and and re-write it.

I remember my reaction when I read those words. It was something like, “Are you kidding me?

“Do you know how much time and effort and energy I put into writing my first novel? Do you know how HARD I worked to make that book as good as it could possibly be? How can you tell me that there is ANYTHING I can do to make that novel any better?”

And so I made my peace with deep-sixing Libby forever. After all, I believe looking forward, not back!

On the other hand, I’ve always loved the novel’s premise. And it’s my favorite type of book to write: a book that set in the real world but admits to paranormal elements. And has romance. And family.

Kind of like real life ;)

So this spring, I picked Libby up and looked at it again for the first time in seven years. And guess what?

The readers were right.

Not in their specifics. They’re readers, not writers. They didn’t really understand why they didn’t like the book.

But since pubbing Libby, I’ve written several other novels and a ton of short fiction. And — even more important — I’ve read, and re-read, dozens of books on the craft (which I’m slowly reviewing for my blog; if you’re interested look here and here).

I’ve learned things. And because I’ve learned things, I could now see huge problems in Libby that I’d missed back when I was laboring away at the novel in 2010, 2011.

So this spring, I took that long-ago advice and began a re-write. Practically from scratch.

I changed a lot.

I switched the voice from third person to first.

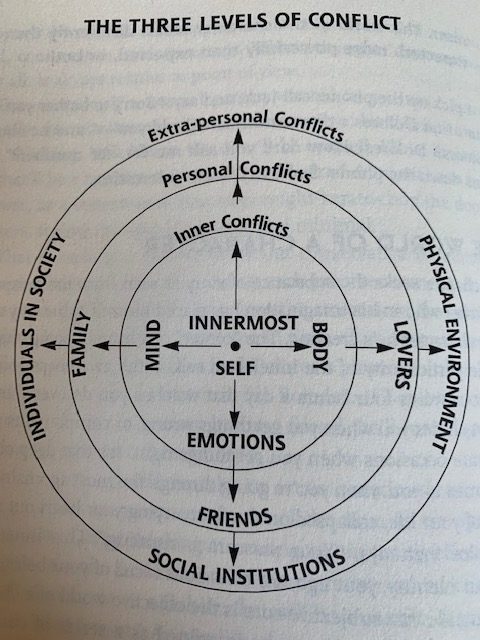

I did a major deep-dive into my characters’ motivations — especially Libby’s — and re-wrote plot points to better articulate why they do what they do. (This was critically important with regard to one of the reasons readers disliked the last edition of the novel. They didn’t think Libby showed agency. This criticism baffled me at the time. After all, I knew why she made the choices she did! But I hadn’t done my job, as a storyteller, to reveal her motivations — so to readers, she came across as weak — a pushover.)

I tightened scenes that dragged. I created new scenes to add more texture and depth to the story.

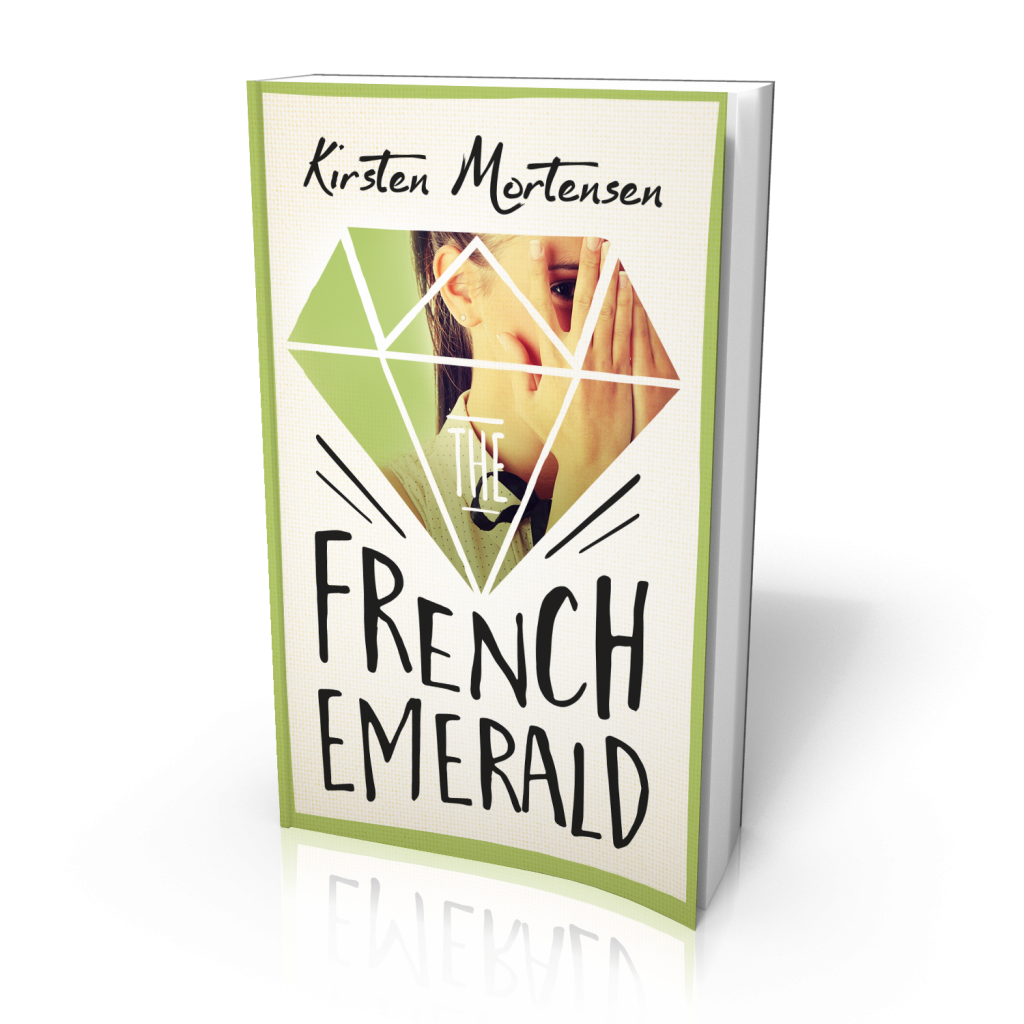

And I found a designer (Lara Wynter) to re-do the cover.

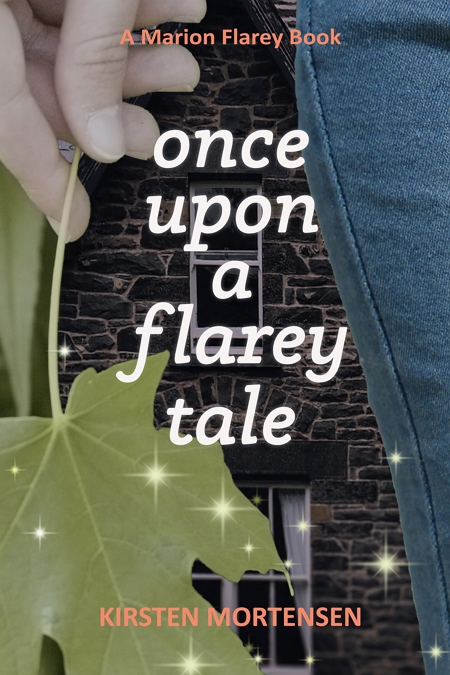

And on October 23, I’m re-releasing Libby.

I have mixed feelings, to be honest. My experience in 2012 was incredibly humbling. I’m one of those writerly people who’s been told, my whole life, how good I am. “You’re such a good writer.” I’ve heard that a million times. It was hard to find myself being pilloried — to find myself being told that I was a total loser.

But I’m also hopeful that I’ve made enough progress as a writer that I can redeem this failed novel and turn it into something that readers will love.

Because, after all, that’s what I’m trying to do. Write books that readers will love …

Welcome back, Libby … wishing you the best of luck.

She’s seeing things that don’t exist.

Her boyfriend thinks she’s crazy.

And then the Internet found out.

When Libby Met the Fairies. E-book available now for pre-order at the sale price of only $2.99. Click here to browse available formats and place your pre-order!