Writers gonna write.

But as long as we’re all stuck at home during this pandemic, we can do more than just put out words, right? We can also work on our craft.

So in the spirit of sharing w/ my fellow writers, I thought I’d share a bit about some of the books in my writing-craft library.

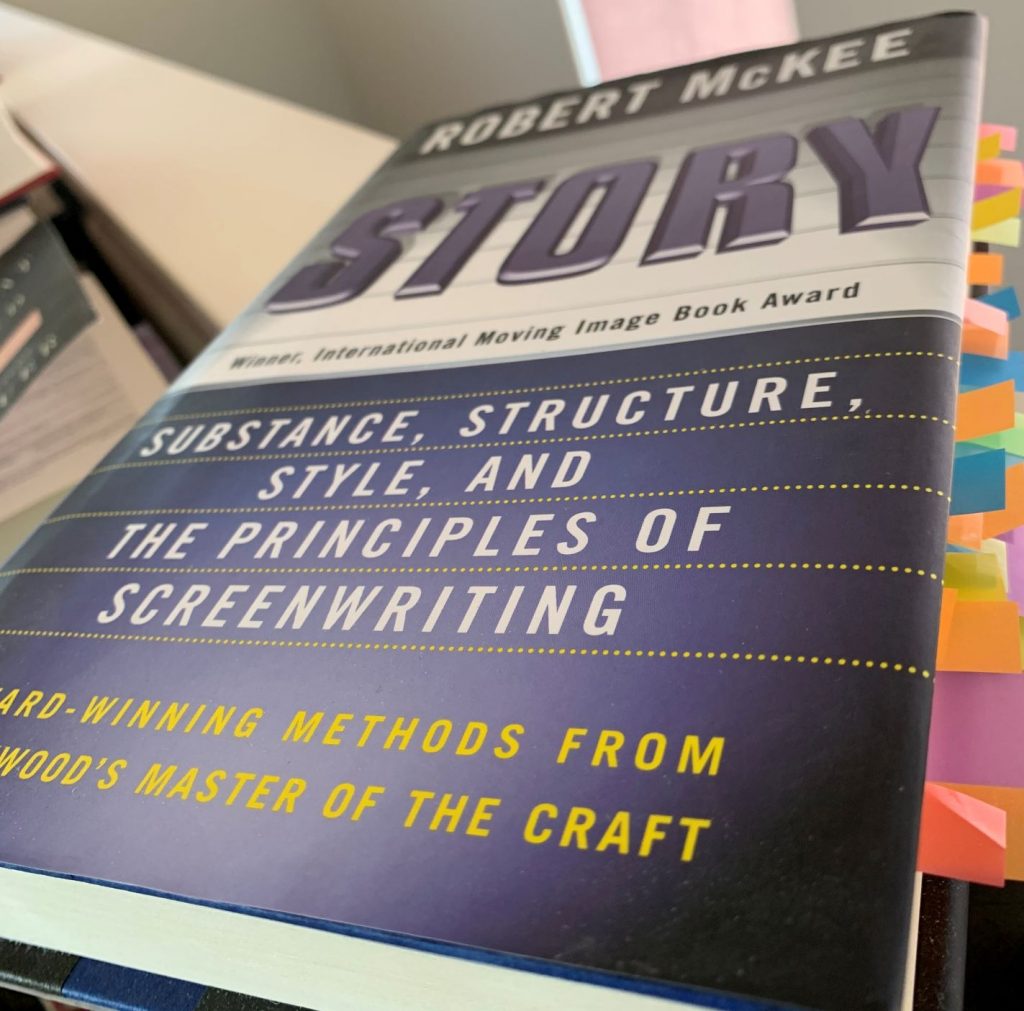

First up, Story, by Robert McKee.

This is one of the more recent additions to my library. I bought it last year as I began work on my current WIP, Once Upon a Flarey Tale.

As you can see from the pic, I use sticky tabs to mark parts that I expect I’ll want to review again–and there are a lot of sticky tabs in this book :)

What You Need to Know About Story (In No Particular Order!)

McKee is a screenwriter, not a novelist. But the building blocks of movies and contemporary novels are so similar that you shouldn’t let that put you off–you’ll find a lot of terrific information here that will help you tell better stories, regardless of the medium you use to tell them.

McKee is a teacher, lecturer, and consultant. Reading this book is a lot like attending an upper-level class on story-telling.

It’s hefty. 418 pages — there is a LOT here. Which is a good thing, IMO, because the more I learn about this craft, the better. Just don’t plan to finish this one in a single sitting ;)

It’s comprehensive. You’ll find everything in this book from the basics of the classic 3-Act story structure to how to develop character motivations to what makes a good title.

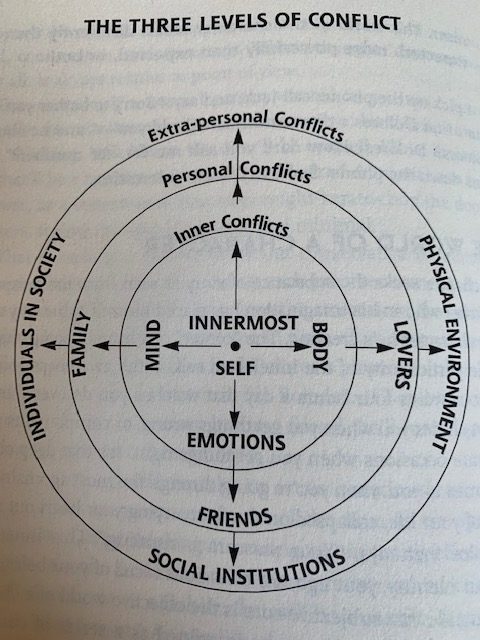

Story includes a lot of highly conceptual models for understanding how to make stories work. If you’re the sort of person who benefits by seeing concepts modeled visually, you’ll find a lot of tools to your liking in this book.

The Notes I Jotted Down / Passages I Flagged

In no particular order:

“Story values” are universal qualities of human experience — and they always have polar opposites. Examples are “wise” and “stupid” or “alive” and “dead.” Every scene will have at its heart some value; in ever scene, that value should change. And if the value doesn’t change, it isn’t a scene, it’s exposition — and it needs to be cut.

To avoid cliche, master the world of your story. This was a cool insight, I thought, because when you are completely immersed in that world and relating what you see, you won’t use other peoples’ commonly repeated words — you’ll use your own, the words you invent as you look around.

Research your stories in three ways: by unleashing your powers of memory; by unleasing your powers of imagination; and by what we usually think of as research — chasing down facts.

Create a finite, knowable world. “The world of a story must be small enough that the mind of a single artist can surround the fictional universe it creates and come to know it in the same depth and detail that God knows the one He created.” McKee comes back to this same idea later in this way: “design relatively simple but complex stories.” He then explains that by “simple” he doesn’t mean simplistic, but that we should avoid the temptation to proliferate characters or locations in an undisciplined way. Instead, constrain yourself to a “contained cast and world” and focus on building complexity within that world.

But at the same time, you need to create much more material than you will ever use–five times what you use, or even 10-20 times. An example from my current WIP: I’ve written fairly details timelines of each of my character’s lives, matching them to world events as well as personal milestones. Most of this will never make it into my books, but it gives me a wonderful send of fully knowing my characters.

Don’t be afraid to abandon your original premise if you discover, as you build your story, that it doesn’t work any more. (Phew!!! Because yes, this seems to happen to me a lot!)

Related: a story “tells you its meaning.” You don’t dictate the meaning to the story …

Inciting incidents should arouse unconscious as well as conscious desires in our protagonists.

“The most compelling dilemmas often combine the choice of irreconcilable goods with the lesser of two evils.” Related: “True character can only be expressed through choice in dilemma.”

Effective scenes operate at the levels of both text and subtext.

Progression in the story is built from cycles of rising action.

“When a story is weak, the inevitable cause is that the forces of antagonism are weak.”

“Never use coincidence to turn an ending.”

We interrupt this post to remind you that I have a new book out. And it’s the best book I’ve ever written. Available on Amazon for print or Kindle, or click here to browse other e-formats.

Character dimension springs from that character’s internal contradictions. But those contradictions must be consistent. “It doesn’t add dimension to portray a guy as nice throughout a film, then in one scene have him kick a cat.”

“To title is to name. An effective title points to something solid that is actually in the story.”

What I Liked About Story

This book is so obviously the culmination of many, many years of McKee’s work, teaching the craft of story-telling. There are countless nuggets in here that writers can grab and put to use to improve the quality of our novels.

What I Didn’t Like So Much

So much of what McKee conveys, he does so using conceptual models. The danger for me is that if I get caught up in understanding the model, I lose track of my most effective compass as a writer, which is based on feel: on how I react to something I’ve put down on the page.

How about you? Have you read Story? Do you have a favorite writer’s craft book that you would recommend?

UPDATE: Click here to read the next post in this series where I review Writing the Breakout Novel by Donald Maass.