It’s long past time to draw a line between actual data and fantasy “models” — and set public policy accordingly

Over on Facebook, I linked to an essay by the Swedish writer Malcom Kyeyune titled Why the Experts are Losing, which elicited this comment from a (dear) friend:

So, when dealing with complicated things, who should one listen to if not someone who actually knows the topic? And what should one look at besides data?

The comment got me thinking about data.

Specifically, it got me thinking about a mistake that I think people make when they look at “data” and “research consensus” as the basis of their policy preferences.

Because of course we need to base policy on data.

But many people are making a huge mistake when they cite “data” — a mistake that is tied closely to our reliance on “experts.”

There is a WORLD of difference between “data” that is based on actual reality — meaning data collected on something that has happened — and “data” that is generated by computer modeling — meaning “data” that predicts something that is supposedly likely to happen in the future.

Models are not reality.

It’s my observation that many people overlook that distinction…

…And overlooking that distinction is a major source of policy mistakes over the past few decades (dating back to when researchers began using computers).

I also believe it’s related to another concept that I’ve been noodling for many years: the problem of abstract thinking.

It seems to me that we moderns, perhaps particularly moderns in the West, have prioritized *abstract* thinking to the grave detriment of *reality-based* thinking.

I suspect this is the result, at least in part, of our push to position “getting a college education” as the one and only pathway to professional and personal success, a.k.a. “fulfillment.”

We’ve churned out several generations of people who’ve been trained to think that if you read “about” something, that counts as actually knowing that thing.

News flash: it does not.

Which is why, sadly, many of the people who we have elevated to the position of “expert” are not experts at all. They are, to be blunt, fools. And they don’t know it. They will stand there, flat-footed, like the fool Ned Price did in a recent, disastrous state department press briefing, seemingly unable to grasp that asserting something is true is not the same as presenting evidence that a thing is true.

“I said it. That’s the evidence.”

Who thinks like that?

“Experts” who are in fact fools.

Starting them young.

Our predicament may also be a result of modern pre-K and elementary school institutional norms.

I’m influenced in my thinking, here, by the work of the late Joseph Chilton Pearce, who proposed in his book The Magical Child that we’ve made a huge mistake by emphasizing literacy (specifically reading) at too young an age.

For children under age seven or so, we now push “literacy” at the expense of actual, hands-on, touch-and-feel experiences with physical phenomenon.

And this arrests our children’s healthy development.

Young brains, Pearce argued, are designed to master reality by being immersed in the physical world — by touching it, tasting it, moving within it — not by learning “about” it.

When we inappropriately insert abstract thinking into a child’s “training,” we set that child up for problems later on.

One of those problems is chronic anxiety.

My books are all still in storage. I can’t cite specific passages of Pearce’s book. I’m going from memory.

But this is an important enough point that I’ll elaborate.

How to raise an anxious child

Suppose that you are an aggressively protective parent, and to ensure your child will never suffer a burn, you decide to never, ever allow the child to touch anything that is hot.

Instead, you teach the child about “hot” by monitoring the child and shouting “don’t touch!” (stove burner), “don’t touch!” (water from the faucet), “don’t touch!” (pizza from the microwave) any time the child gets close to a hot thing.

You think you’re keeping the child safe. And perhaps, in one sense, you are.

But there’s a couple (related) problems.

1. A child raised this way learns he/she must check in with you continually to see if things are safe, instead of figuring anything out via first-hand exploration.

And 2., the child loses out on a critical aspect of development: he/she never learns that it’s safe to freely explore the world.

Don’t misunderstand me. I’m not saying parents should let their children play in traffic to learn that being hit by a car will hurt.

Parents need to set up guard rails while their children explore the world.

Set up guard rails, then let the child bump into things within that space. This allows the child to learn by accruing direct, first-hand experience with physical reality.

Learning directly from physical reality has value in its own right. The child gains confidence in his/her own judgement. The child learns what “hot” really is. (If you’ve ever raised a child, you also know that “hot” is a lesson a child only has to learn once — a lesson delivered directly from the hand of Mother Nature is a very powerful one.)

Conversely, if you teach a child that, to be safe, he/she must check in, constantly/continually, with the Big, Powerful adult, you do a number of not-so-ideal things to that child’s mind-brain.

You add a layer of processing to the child’s interpretation of the world which is based, not on reality, but on an external (to the child) interpretation of reality, which the child ingests second hand. The child learns to operate in what is essentially an abstraction: a second-hand model of the world, instead of the actual world.

That is anxiety-inducing. In simplest terms: the child internalizes the “lesson” that he/she doesn’t have the ability to understand, through primary means, what is dangerous and what is not.

When the child becomes, physically, an adult, this lesson becomes an unconscious assumption. The person will believe, on an unconscious level, that he/she lacks the power to keep himself/herself truly safe.

On an unconscious level, the person will never really trust his/her ability to know that something is hot. He/she only knows that there are dangers out there, lurking. And he/she will, unconsciously, be continually scanning for a Big, Powerful Parent to protect him/her from the invisible dangers.

Which leads us to another issue.

What happens when the parent is no longer there to yelp “don’t touch”?

I think we’re finding out.

Welcome to America the Frightiful…

It’s no big secret that anxiety levels among us Western moderns have been rising.

This predates COVID. Medical News Today reported wrote in 2018 that 1 in 5 Americans suffer from anxiety disorders.

It’s also pretty widely known that anxiety disorders, as a phenomenon, is worse among younger people. Anxiety in children and teens rose 20% between 2007 and 2012. Per this article by the American Psychological Association,

Both Millennials and Gen Xers report an average stress level of 5.4 on a 10-point scale where 1 is “little or no stress” and 10 is “a great deal of stress,” far higher than Boomers’ average stress level of 4.7 and Matures’ average stress level of 3.7.

People blame social media and screen time and, now, social isolation.

But perhaps the actual problem is something else.

Perhaps the root cause is that we fail to give young children the experiential stimuli they need to develop baseline levels of physical courage.

Quite a thought, eh?

And then, along comes a scary computer model…

So, take a population of people who are viscerally anxious all or much of the time.

A population of people who have never learned to trust their own eyeballs — their own 3D experience — in some fundamental sense, to discern what’s going on in the physical world.

Turn them loose in our academic and government institutions — because they all went to college and got degrees in fields that deal almost exclusively with abstractions.

Ask them to study the world and come back and tell us what to think about it.

And lo and behold, they discover the computer model.

They write software programs — algorithms — that ingest numbers and then spit out predictions.

And — lo and behold — some of the predictions are terrifying.

In a recent example, one computer model that got a ton of press in 2020 projected that, unless we embraced severe lockdowns, enormous numbers of people would die from COVID.

2.2 million in America alone.

That model hit us like a freaking nuclear bomb.

The waves of panic it generated are still wracking us today. People today are still hiding in their homes.

And why?

Because a substantial subset of people reacted to the model as if it was real, instead of what it actually was — an abstraction. A mental construct.

They reacted to the model as if it was data about something that had happened, instead of being able to step back and recognize the trust.

The model was idea about something that might or might not happen.

And people panicked.

And other people took advantage of the panic to get themselves in front of the television cameras, and make themselves out to be heroes, and get their grubby paws on even more money and power.

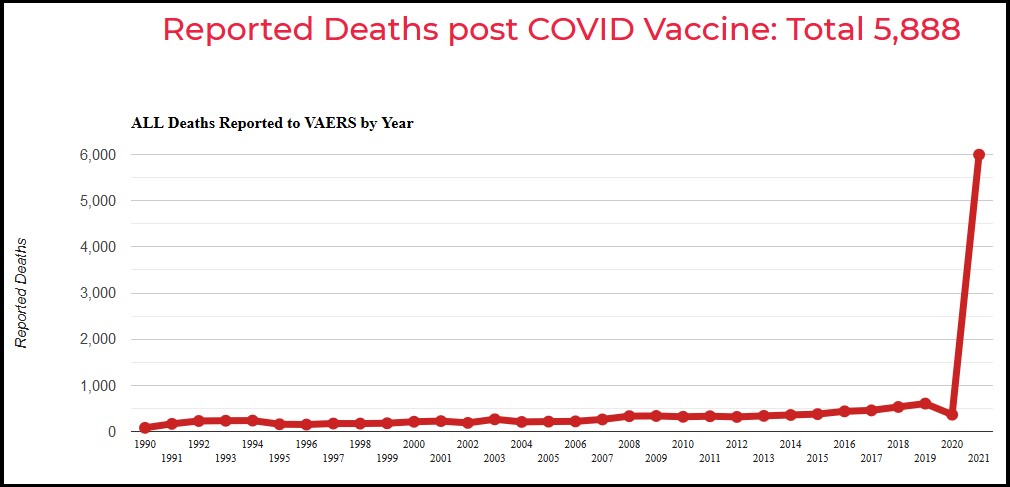

Now. Compare the Imperial College modeling to the data that actually comes out of the real world, relating to the COVID vaccinations.

You have VAERs, for example — the CDC’s Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System.

Is that not “data”?

Oh, but it’s not “clean” data, people argue. Anyone can upload a report of an adverse effect. You can find, if you look, reports that are obviously barmy.

Google VAERS+COVID and you’ll be swamped with “fact checks” that assert that the spike in reports of adverse effects that is showing up in the VAERS database is nothing more than a mirage. A meaningless artifact.

Right.

In other words, we’re supposed to believe the fact-checkers’ narrative about the “data” instead of becoming curious about what the data suggests.

Hint: something is terribly wrong with these vaccines.

And wait. There’s more — more than just VAERS.

What about the DoD data that was reportedly leaked to attorney Thomas Renz? Renz testified recently to a Congressional panel that the DoD medical claims data he has in hand shows a clear and horrifying increase in a range of medical problems.*

(*The database he cites was subsequently altered and no longer shows the same spikes.)

The increase coincides with the rollout of the COVID vaccine.

We’re talking huge jumps in miscarriages, neurological disorders, cancers.

And what’s this about insurance companies reporting spikes in all-cause mortality — spikes that correspond to the vaccine roll-out?

I saw another story recently, and am sorry to say I lost the link, but it was data released by a publicly traded funeral home company. It also showed a steep rise in all-cause mortality. Corresponding in time to the vaccine roll-out.

And did you know that when Pfizer ran its vaccine trials, more people died in the cohort that took the vax than in the control group? From the linked article, by Alex Berenson:

Pfizer told the world 15 people who received the vaccine in its trial had died as of mid-March. Turns out the real number then was 21, compared to only 17 deaths in people who hadn’t been vaccinated.

Once again, we have actual data, gathered from things that have happened in the real world.

And here’s the odd thing.

This may be a bit of an over-generalization, but it seems to me that the same people who panicked when The Imperial College published its model predicting 2.2 million U.S. deaths — people who to this day defend that model — are the same people who insist that the vaccines are perfectly safe. That there is absolutely zero validity to any of the data that suggests that people who take the vaccines are at risk of side effects.

And — again, an overgeneralization, perhaps — this same cohort also seem to me to tend to be terrified by models that predict “climate change.”

You know why it’s now called “climate change,” right? Because the models that predicted “global warming” failed. The temperature increases modelers predicted back in the Al Gore/Inconvenient Truth days never materialized. The Climategate scandal happened because it came out that leading global warming researchers were fudging data.

The effects on observable natural phenomenon predicted back in that same timeframe also failed to materialize. In fact, it’s an ongoing source of mirth in some circles, to this day. Britain is still getting snow, Glacier Mountain Park still has glaciers, the polar bears are fine.

So is it a coincidence that, per a recent Pew poll, the cohort of people who “believe in climate change,” are “pro-vax,” etc. — people who identify as “liberal” — are also more likely, by a lot, to say they have been diagnosed with a mental illness?

I’m not casting aspersions, here, or making light of this. On the contrary, I find this deeply upsetting.

It is tragic.

We apparently have a pretty large (and growing) cohort of Americans who are chronically, viscerally anxious.

This same cohort are also behaviorally conditioned to view the world through abstractions.

That’s the powder keg.

The match is these computer models that predict suffering and death.

This cohort is unequipped to “repel” the computer model.

They react viscerally: they see a doomsday prediction generated by a computer model, and experience a sudden, bodily jolt of alarm or fear.

And this visceral reaction essentially validates that the models are “truth.”

“OMG. I knew something awful was lurking out there! And this model proves it!”

And this means several things for the rest of us.

First, we have brothers and sisters out there who are terrified.

That’s awful.

What’s equally awful is that they want everyone else to be terrified, too.

It’s understandable. Human nature. If everyone else isn’t terrified, that’s essentially a reproach.

It makes the frightened ones look like they’re over-reacting and foolish. And nobody likes to look foolish.

And quite frankly, sometimes frightened people deal with the not-frightened by becoming mean. They lash out. So you get the name-calling. “Climate deniers” and “racists” and “anti-vaxxers.”

These names have nothing to do with the actual beliefs held by the people they’ve labeled. But that’s not the intention. The intention is to other and to scapegoat.

It temporarily relieves peoples’ anxiety, I’m sure. I’m also sure that, under the right circumstances, it could evolve into something much darker, like we see in countries like Australia and Austria and Lithuania where “anti-vaxxers” are now functionally second-class citizens. Being punished by the Righteous.

The Believers, insofar as they influence the media and our overall perceptions of reality, also push us into adopting destructive policies. The lockdowns are a terrific example. A new research study by Johns Hopkins, for example, concludes that lockdowns had only a tiny effect on COVID mortality rates — but a large impact on the economy and peoples’ mental and physical health.

Some of us predicted this from the beginning.

Common sense. COVID is a respiratory virus. Once it’s out in the population, it’s going to spread. Locking people down might change the speed and distribution of the spread, but logically it can’t stop it.

Common sense. Locking people down will disrupt businesses, fray social networks, deter people from seeking healthcare.

It was entirely predictable.

But the people terrified by the Imperial College models got their way and swung the giant wrecking ball, and here we are.

The other consequence of all this that troubles me is that when we’re running around panicking about scary models, we’re not paying attention to actual, real-world problems.

We throw all this money and attention at “climate change,” while back in in reality, actual environmental degradation is taking place — issues that we can document right now by gathering real-world data. One example, of many: the U.S. agency that is supposedly in charge of regulating pesticide companies is actually in bed with them.

In a just world, everyone who calls him/herself an environmentalist would be screaming bloody murder about that.

Not happening.

We don’t have the bandwidth.

Too many of us are locked indoors, locked behind our masks, conditioned to believe that our fellow human beings are killing us by reproducing too much, consuming too much, driving too much, farting too much.

Our fellow human beings are actually unclean vectors of death. We can’t even breathe the same air without risking our lives.

What a mess we’ve made of things.

How far we have strayed from the Light and the Love.