What I’ve been doing instead of blogging :-)

(besides working of course! my day job has been pumping writing assignments to me like an out-of-control gadget in an I Love Lucy bit)

is reading.

One book I’ve just about finished now is Shakespeare: The Biography by Peter Ackroyd, and a couple nights ago got to the chapter covering the period where Shakespeare was writing Coriolanus. One of the themes Ackroyd explores is Shakespeare’s use of contemporary political events in his drama; in Coriolanus, there are parallels between the events of the play and the 1607 Midland uprising by English peasants against the landed gentry. Shakespeare displays an empathy with his characters; for instance, he portrays his rioting Roman citizens as motivated by imminent starvation. Nonetheless, notes Ackroyd, Shakespeare didn’t take a political position in the play. Instead, he “displaced and reordered” the events of his own day “in an immense act of creative endeavor.”

Everything is changed. It is not a question of impartiality, or of refusing to take sides. It is a natural and instinctive process of the imagination. It is not a matter of determining where Shakespeare’s sympathies lie, weighing up the relative merits of the people and the senatorial aristocracy. It is a question of recognising that Shakespeare had no sympathies at all. There is no need to ‘take sides’ when the characters are doing it for you.

To take this a step further, consider Norman Holmes Pearson and W.H. Auden’s introduction to Viking’s The Portable Romantic Poets, in which they write:

Consciousness cannot divide its donnes into the true and the false, the good and the evil; it can only measure them along a scale of intensity.

Exactly. And so we have in Shakespeare that he seeks the intensity of consciousness rather than, say, ethical illumination; this explains also why “art” in the service of some sort of Message is invariably off-putting, like a note struck not quite in tune; even though we may nod in approval our jaw has tightened slightly; we are burdened by such “art” rather than released.

As it happens, I’ve also just finished another book, A Disorder Peculiar to the Country, by Ken Kalfus, which the book jacket promised to be “rollicking” and “a brilliant new comedy of manners.” The book, if you haven’t heard, is set against the backdrop of 9/11 and its aftermath; the plot is the bitter interplay between a man and wife who are divorcing. It was a 2006 National Book Award Finalist and got press when it was published for having incorporated 9/11, and for the opening hook: both protags believe for a short time that the other had perished that morning, and hate each other so much they both hope it to be true. And so you have the frisson of public horror mixed with private triumph, raising the possibility that the book will somehow conflate or even alchemize public and private worlds, public and private reactions. It’s a book, IOW, that suggests we will find some sort of Meaning, if only of the sardonic sort.

And so I read, hunting. Here’s a bit of what I found: a reference so passing as to almost seem inserted (as if the actual event occurred as Kalfus was drafting the book; it didn’t, it actually happened before 9/11, although in the book, whether by error or literary license, it’s said to have happened in 2002) to a suicide bombing of a pizzeria in Tel Aviv. Marshall is reminded of the bombing when he’s walking in Manhattan and is startled, post-stress-syndrome-traumatically, by the sound of a “heavy steel grille being slammed shut on the back of a truck parked in a loading zone;” he goes on to reflect:

This was a world of heedless materialism, impiety, baseness, and divorce. Sense was not made, this was jihad: the unconnected parts of the world had been brought together and made just.

So Marshall’s personal world is allegorically connected to international events. Nod, nod.

Earlier in the book Joyce, the wife, again in a scene that felt to me patched-in, is said to be “intently” following the invasion of Afghanistan — so much so that she memorizes the country’s geography, the better to follow the military campaign’s every move. She’s also “drawn to the Afghan people, for their beauty and primitive dignity, even if that dignity seemed contradicted by their brutality, untrustworthiness, and venality” and asks

Would American wealth and the expediencies of its foreign policy corrupt the Afghan people? Or were we being corrupted by their demands for cash, their infidelities, and their contempt for democratic ideals?

Meanwhile her life hadn’t changed. She was still not divorced and she had lost hope of ever being divorced; or, more precisely, her marriage was a contest governed by one of Zeno’s paradoxes, in which divorce was approached in half steps and never reached. After the long post-9/11 interregnum, Joyce and Marshall had resumed meeting with the lawyers, who themselves seemed wearied by their disputes despite the cornucopia of billable hours.

You can almost hear the study questions forming in the background. How does the Afghan invasion shed light on Joyce’s behavior toward her husband? Her attitude toward her divorce? How she views herself within her marriage?

And of course there’s also the possibility that we’re intended, as well, to find Kalfus himself peeking through, a kind of parallel world outside the book where he is wink wink nudge nudge “taking sides.” More study questions.

What we don’t find, however, is intensity. There’s the Jerry Springeresque viciousness of Marshall and Joyce’s mutual hatred, but that’s not intensity, that’s spectacle. Certainly neither Marshall nor Joyce “take sides” in contemporaneous political questions, unless moral ambivalence itself counts today as side-taking.

We’re left with mere Meaning.

It’s enough to make one wonder if that’s the most to which a literary writer, writing in America today, can dare aspire.

Related: I also blogged about The Portable Romantic Poets here.

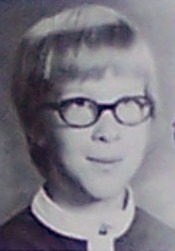

The body is always in a state of flux, of course, and once pointed in the direction of poor vision dutifully explores that trajectory; the silver lining was that as my eyesight worsened I swapped the hornrims for gold wire rims, and later contact lenses. Not quite so homely.

The body is always in a state of flux, of course, and once pointed in the direction of poor vision dutifully explores that trajectory; the silver lining was that as my eyesight worsened I swapped the hornrims for gold wire rims, and later contact lenses. Not quite so homely.

Susan has sent me some more pics of Camilla to post here. Look at that sweetie! She doesn’t look at all like a dog who would chew a slipper now, does she!

Susan has sent me some more pics of Camilla to post here. Look at that sweetie! She doesn’t look at all like a dog who would chew a slipper now, does she!