Writers want to support other writers, but when it comes to leaving reviews, we’re torn. What if we don’t like a book? What if we spot flaws? Fortunately there are options — if we change the way we think about “reviews.”

If you’ve ever hit the “publish” button on Amazon or Smashwords or D2D, you know how terrifying it is to put your novel out there for everyone to see — and judge.

You also know how badly you need reviews.

And as you meet other writers on Twitter or Facebook or Instagram, chances are you’ve faced another dilemma: should you review other writers’ books? And if you’ve read a book and don’t like it — or, worse yet, spot what you think are flaws — what should you do? Share your thoughts publicly? Contact the writer privately? Drop the whole thing and enter the witness protection program? All of the above?

As a writer, you know first-hand how much negative reviews hurt.

Negative reviews dampen sales — and that’s not even the worst of it. Getting a negative review is personally painful for writers. It’s discouraging. No matter how thick-skinned we try to be, it feels so, so personal.

On the other hand, you also know the importance of feedback.

I speak from experience! As much as I hate negative reviews, I learn a LOT from them. I get data from negative reviews that helps me become a better writer and better understand my audience.

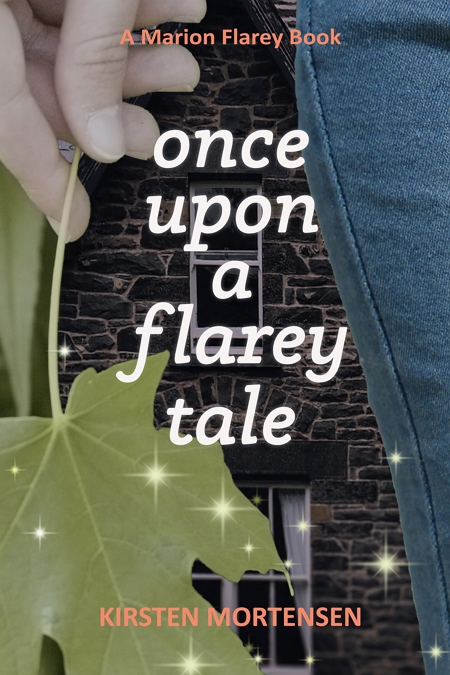

I’m currently doing a completely re-write of a novel based on input I got via negative reviews. Yes, those reviews tanked my rankings. I was just starting to get traction as an author, and poof. Everything I’d built was gone; years later, I still haven’t fully recovered. But when I’m done with the revision, the novel will be a better book. MUCH better. (If you’re interested in this story, by the way, stay tuned. I’ll be sharing more about it in a future post.)

In other words, there’s nuggets of gold buried in negative reviews, if you can stomach looking at them.

But that doesn’t mean that writers should use reviews to point out flaws. Especially when there are other ways to support each other. Better ways.

A New Framework: Review, Endorsement, or Critique?

As writers, we need to get more comfortable — even a little cynical — with what we all know is true. Reviews exist because the platforms where we sell our books use reviews to drive sales.

Reviews may benefit authors, too, but that’s not really why Amazon lets us post them. Amazon lets us post reviews for one reason only: because it’s good for Amazon!

Writing and posting reviews also requires us to invest time and energy. When you publish a review, you’re creating content and giving it away. Sometimes it makes sense to do that. But every minute you spend creating content to enrich the Amazon platform is time you could have spent working on your novel.

Fortunately, there are two other ways to support our fellow authors.

The first way is an endorsement. You publicly praise a book and recommend it to others.

And see what I did there? Because guess what. You can use a review to make an endorsement. But all that really means is that reviews are a vehicle for publishing endorsements. It doesn’t change the fact that reviews and endorsements are two entirely different animals.

In fact, when I stopped mixing up the concept of “review” with the concept of “endorsement,” I saved myself a ton of headaches, because the question “review or not review?” is now extremely easy to answer.

“No. Nope. And no.”

I never just “review” other writers’ books.

Instead — time permitting — I sample read other writers’ books, and sometimes buy and read other writers’ books, and then, if I really like something I’ve read, I’ll endorse it. I’ll post an endorsement (what everyone else calls a “positive review”) on Amazon. I’ll sometimes share my endorsement in other ways, e.g. Twitter.

“But Kirsten,” you say. “What if I read another author’s book and for some reason I don’t feel I can endorse it?”

Glad you asked, because that leads me to the last category: critiques.

Critiques, unlike reviews, are private. They’re feedback — just like negative reviews are feedback — but they don’t embarrass the writer or hurt rankings and/or sales.

I’m a lifelong reader and a lifelong professional writer. I’m also a self-published author who has been working on novels for over twenty years, now.

I’m far from perfect! But when it comes to novels, I’ve learned a little bit about what works and what doesn’t. And I’ll be blunt: I immediately spot serious flaws in the majority of self-pubbed novel I sample.

Am I going to buy a flawed indie-pubbed book, slog through it, and post a public review that details its problems?

Hell, no.

Because who would benefit?

Not me! I’d be taking time away from writing and from reading books I actually enjoy — not to mention the rest of my life.

And certainly not the writer! See above. Negative reviews do real hurt. And what writer wants to hurt other writers?

On the other hand, if you came to me and asked me for an HONEST critique, I’d read a few pages and don my fire suit and tell you what I honestly think could be made better. Even though, mostly likely, you won’t like it. Even though there’s a very good chance you’ll think I am completely wrong and don’t understand your book and don’t understand you as a writer or what you’re trying to do and everyone else who’s looked at your book told you it’s AMAZING.

I know you’re likely to respond that way, because that’s the way I respond to “negative reviews” (which are actually critiques … by people who have chosen to make them public).

But I’d be supporting you in a way that is a lot kinder and more useful than pretending your book is wonderful when it’s not, or telling the world I think your book has issues …

Or staying silent.

So, what do you think?

Maybe, instead of committing to public reviews, we could start offering other writers either:

A. Public Endorsements or

B. Private Critiques …

We’d be helping each other.

We’d be avoiding sticky promises that make us feel deeply uncomfortable.

We’d avoid hurting each other.

What do you think?