An author ought to consider himself, not as a gentleman who gives a private or eleemosynary treat, but rather as one who keeps a public ordinary, at which all persons are welcome for their money.

— opening sentence in the novel “The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling,” by Henry Fielding, 1749

Shakespeare relied upon the audience and, with such devices as the soliloquy, extended the play towards it; the drama did not comprehend a completely independent world, but needed to be authenticated by the various responses of the crowd.

— Shakespeare, The Biography, Peter Ackroyd

I’ve broken a rule in my latest self-pubbed novel , and I’m worse than unrepentant. I’m defiantly unrepentant. It’s the rule forbidding “authorial intrusion.” Here’s how my novel opens.

, and I’m worse than unrepentant. I’m defiantly unrepentant. It’s the rule forbidding “authorial intrusion.” Here’s how my novel opens.

There are a ton of stories about it floating around on the web. Half of them are baloney. The other half—baloney and cheese.

The woman is a biologist. A trained scientist. Meaning: for her, things either stack up to the measure of the five senses or you brush them aside.

So forget what you’ve read.

Forget what you’ve read from people who say she’s some kind of New Age Messiah.

And while you’re at it, forget the stuff that denounces her as a cynical fraud.

Here’s what really happened.

The book, not by coincidence, is about a woman who discovers she can see fairies. This makes it a fairy tale, and I’ve begun it with my own little twist of Once Upon a Time.

Which makes me, of course, a Bad Writer.

I wouldn’t have been judged so harshly a couple centuries ago. There was a time when authorial intrusion was not only accepted, but expected. Not today. Today, if you were to pester an agent or editor with a novel that opens like mine, your book would go straight to the reject pile.

Now I’m not saying this new novel I’ve pubbed is good. On the contrary. A) It’s not my place to say whether it’s good. And B) the experience of attempting fiction is a humbling one. Writing a good novel is extraordinarily difficult. And having finished four, I am still only a rank beginner.

It would be presumptive of me to suggest I’ve managed to produce anything that might be objectively described as “good.”

So my thoughts on authorial intrusion, or any other stylistic convention, don’t carry any particular authority. But hell. This is the Internet, and I have an opinion ;-)

It goes something like this.

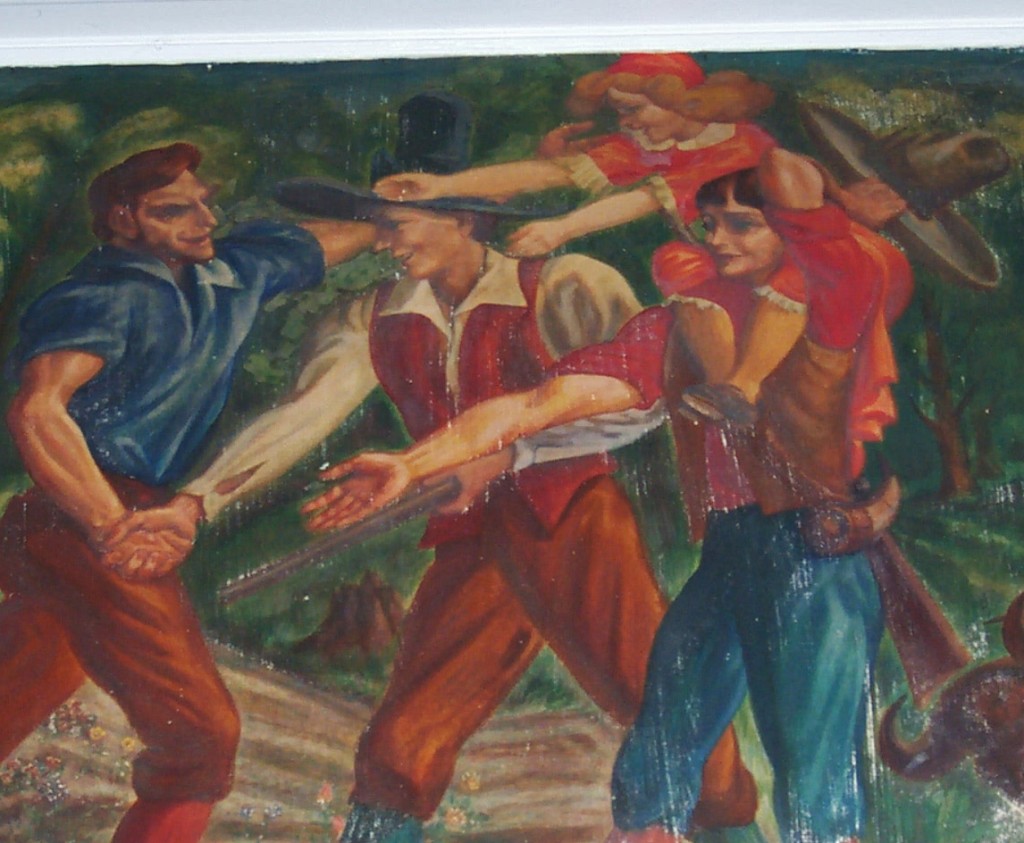

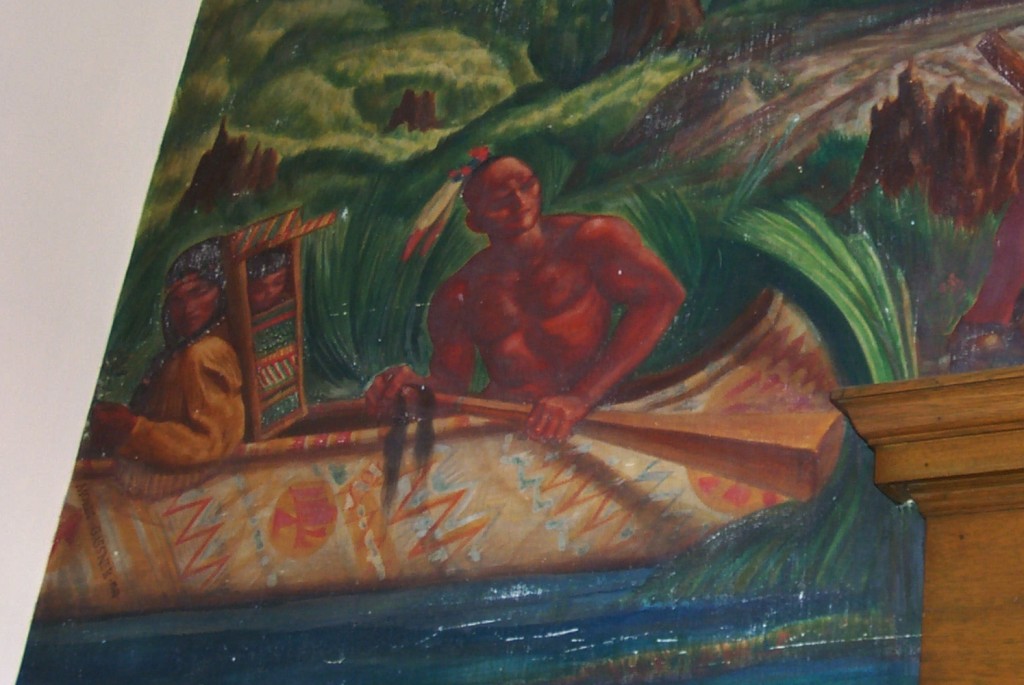

There was a time when fiction was closer to its oral roots.

Before the emergence of a literate middle class, stories were told, not read, and the teller — the author — was therefore a part of the experience. It doesn’t take much imagination to put yourself in a village square in the 12th century, somewhere in Europe, where a small crowd has gathered around someone telling a story — relating an account of some battle, perhaps, or the death of a monarch, or a shipwreck, or pirate raid. A person gifted with a sense of timing, and an expressive vocabulary, a sense of how to play the audience’s emotions, would hold their interest longer. People would ask the speaker to repeat the story. The story teller would gain a reputation, would become sought-after.

And then there were the tales that were repeated orally, the epic poems and fairy tales. Why are there so often multiple versions of these stories? Because some of the people who got their hands on these stories changed things, edited things, added embellishments. These were the storytellers who knew how to juice the plot, how to better engage listeners.

Early novels translated this oral experience to paper.

When Fielding begins the tale of Tom Jones, he does so by inviting the reader to come into a public house, put down a bit of money, and have a listen. Fielding is there, in the room, not self-consciously but because it’s assumed he should be there. It’s Fielding, telling the story; reading his novel is simply a way of inviting him into your drawing room. There’s no 20th Century conceit that he be invisible, that the story is somehow “a completely independent world.”

So what happened?

Why did authorial intrusion become taboo?

I’m no lit scholar, but I can hazard a guess. As more and more people fancied themselves novelists, the pool of second- and third-rate novelists grew. And many of these writers handled authorial intrusion clumsily.

You’ve probably come across an example, if you’ve ever picked up a badly written 19th century novel in a thrift store. It can be extremely off-putting to find yourself lectured by some long-winded boor in the middle of what is supposed to be a novel.

But our fiction taste-setters haven’t decided that authorial intrusion is taboo only if it’s badly done. They’ve made it taboo entirely. The reason for this (they say) is that authorial intrusion breaks the spell. Even the phrase itself suggests a despoiling: something intrudes on that “completely independent world;” the author has become an interloper, a violator.

Again, I agree that if done badly, authorial intrusion can spoil the mood.

But how strange that in, say, television dramas or comedies, the Fourth Wall is no longer off-limits, but in fiction it’s assumed the reader must be continually immersed in an alternative world; that the experience will be ruined if the author calls attention to the fact that the work is fiction, the characters are fiction — that you’re reading an invented tale spun by another human being.

Perhaps we’ve lost the ability, as novel readers, to switch back and forth from “suspension of disbelief” to an awareness that that novels are actually a collusion between reader and writer.

But I don’t think that’s the case.

Our literary gatekeepers have done too good a job at screening fiction against a master list of taboos.

And as a result, writers haven’t had the option of experimenting with authorial intrusion. We don’t know when it works, or doesn’t work, because it’s a tool that’s been locked away.

And that’s too bad.

Christopher Hitchens has a new piece up on Vanity Fair that you’ve maybe come across. [UPDATE: link sadly no longer works…] Hitchens’ cancer has now progressed to the point where it is destroying his vocal cords. The piece is about the interconnectedness of self/personality, writing, and voice. “To a great degree, in public and private,” he writes, “I ‘was’ my voice.”

And now that he’s losing his voice, he appreciates how much the quality of writing depends on the quality of one’s speaking.

In some ways, I tell myself, I could hobble along by communicating only in writing. But this is really only because of my age. If I had been robbed of my voice earlier, I doubt that I could ever have achieved much on the page.

He closes the piece with advice for writers, starting with this:

To my writing classes I used later to open by saying that anybody who could talk could also write. Having cheered them up with this easy-to-grasp ladder, I then replaced it with a huge and loathsome snake: “How many people in this class, would you say, can talk? I mean really talk?”

The ability to hold an audience’s interest orally is no different than the ability to hold an audience’s interest on the page.

Now in the oral tradition, speakers used literary devices to invite their listeners into a fictional world. But it’s silly to assume that once you were past the “once upon a time” gate, the story teller never again “intruded.”

Of course they did. “Once upon a time” the spinner of tales was an active participant in the experience, casting a spell, then withholding it, teasing, making promises and then pretending to back off of them — like the grandfather reading the story in Princess Bride, interrupting a scene to tell his grandson not to worry, Buttercup doesn’t get eaten by eels. Yet.

Authorial intrusion was once part of the experience.

Not only that, but it added to the listener’s pleasure — just as Fielding’s greeting adds to the pleasure of reading Tom Jones.

So yeah. It’s a shame we’ve thrown out this particular baby on account of some stinky Victorian bathwater. But maybe now that indie authors are retaking the industry, we’ll see some authorial winking and nudging inserted here and there.

And maybe readers will actually enjoy it.

Maybe writers will begin to understand that the notion of a “completely independent world” is itself a conceit, and in some respects an increasingly tiresome one.

Maybe we’ll start to realize that authors don’t need to always be invisible.

Maybe we’ll welcome our story tellers back into the room with us, pull up our chairs and start to listen . . .