At some point in fifth grade, I noticed the blackboard in Mrs. Marshman’s math class was blurry. I mentioned it to my parents, and within a few weeks had been fitted with my first pair of glasses.

I didn’t submit to the experience wholeheartedly, by any means. Most troubling was the sense that I was now damaged in some way. Poor eyesight is a mild disability for sure, generally more a nuisance than a crippler. Still, the finality of it weighed on me. It also complicated things. My eyeglass lenses were constantly in need of cleaning, the frames would get knocked about and no longer fit, and then, of course, came puberty, and to my other insecurities came the added burden of a reputation for braini-slash-nerdiness — of which my glasses were an obvious sign.

The body is always in a state of flux, of course, and once pointed in the direction of poor vision dutifully explores that trajectory; the silver lining was that as my eyesight worsened I swapped the hornrims for gold wire rims, and later contact lenses. Not quite so homely.

The body is always in a state of flux, of course, and once pointed in the direction of poor vision dutifully explores that trajectory; the silver lining was that as my eyesight worsened I swapped the hornrims for gold wire rims, and later contact lenses. Not quite so homely.

But I still hated them.

Then I learned about William Bates, an early 20th Century physician who had made the astonishing claim that poor eyesight is learned — and can be unlearned.

I read his book, Better Eyesight Without Glasses, tossed my contacts aside, and began muddling about the world without my visual crutch.

I was encouraged at first. With my eyes freed to function more naturally, my vision improved quite a bit right away; my right eye (the “weaker” of the two) went from 20/180 to 20/80 or so.

But 20/20 vision eluded me. I could induce it for short periods — I’ve passed vision tests, twice, for my driver’s license — but much of the time my world was still blurry. I didn’t put my glasses back on. But sometimes I wondered if the received wisdom wasn’t correct, after all. It seemed that perhaps poor eyesight is inescapable, a curse bestowed by our genes or the modern necessity of being tethered to close-up work, reading, computers.

Now I know differently.

The clues I needed were in another book, Relearning to See, by Thomas Quackenbush. I won’t bore you with the minutiae of my discovery, but the upshot is that I needed to relax and stop trying to see. By trying to see, I was distorting either the shape or the alignment of my eyeballs. When I relax, breath, and stop trying to see, the world around clears.

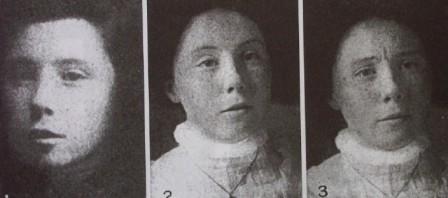

This isn’t a purely physical change. On the contrary, Candace Pert is right on when she says the body is the subconscious mind. Granted, straining to see has a measurable effect on the physical body (this image

is one Quackenbush reprinted from Bates’ Perfect Sight Without Glasses; the woman had perfect vision at the time the leftmost photo was taken. In the middle photo she has myopia — see how her eyes look different? And on the right, she’s furrowing her brow as she tries to see) — but it is first and foremost a condition of being. Put another way: my vision began to blur when I was a child not because my eyes were failing but because as I transitioned from early childhood into social awareness — when I began valuing how others viewed me — a kind of habitual anxiety that defined my relationship to myself hardened into fact. Little wonder the world around me went dim.

When I relax, breath, and stop trying to see, I feel something that affects more than my eyes. It’s like sinking back into a comfortable chair, a state of being in which I am letting go instead of struggling. The clarity of my vision is ancillary: a function of a different vantage point rather than a different way to hold the muscles of my eyes.

Quackenbush touches on this as well in his book, writing:

The individual with blurred vision is interfering with the normal, relaxed way of using the mind and body.

Plenty has been said about the way we modern folk are so stressed; how we react to non-physical stimuli with the same fight/flight response our forebears depended upon to escape saber toothed tigers. But how many of us realize that this response literally distorts our experience? It’s a perversion of our ability to think abstractly: we wrap ourselves in a kind of continual low-grade nightmare, little realizing that our anxiety defines what we can touch and know.

“Cultivate a habit of relaxation.” It’s the first New Year’s resolution on my list, because I’ve begun to understand that everything else flows from it . . .

Geeze why didn’t you start this sooner, think of all the $$ it would have saved your mother and me. :-)

LOL

I do have a little trouble accepting that myopia is entirely psychosomatic.

What about farsightedness that occurs with aging?

Yes, Bernita, it seems like a stretch, doesn’t it. But here’s the thing: we’re talking about tiny little muscles that control the shape and orientation of the eyeball. And to use engineering parlance, the tolerances associated with seeing clearly are very tight — e.g. the portion of the retina that is able to capture an image with crystal clarity is tiny, so even a slight misalignment of the eyeball will result in less-than-clear vision (by causing visual data to fall on the wrong part of the retina) . . . so strictly speaking its not psychosomatic, but more that tension, which can be a result of mental or emotional habits, can affect those little muscles, with the result being a degradation of vision.

Deb, the purists say that presbyopia is also a habit that can be unlearned. There’s less literature on that however — most of the stuff written so far has dealt with myopia or hypermetropia (farsightedness not associated with aging). But wait a few years — as the boomers get their arms around the problem, I’m sure we’ll see more written about it ;-)

(Dontcha love being a trailing edger?)

Pingback: KirstenMortensen.com » Blog Archive » Five alt health trends predictions