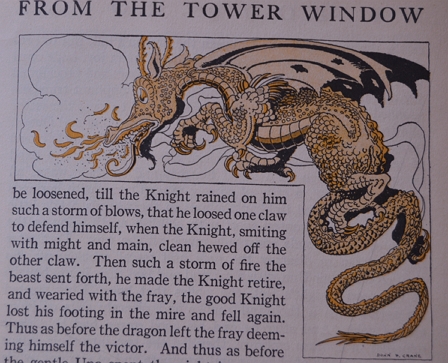

Maybe it’s better to run toward our dragons — instead of running away

I’m struck, so often these days, by how afraid we are.

Why?

What are we so afraid of?

Why do we so often acquiesce to being fearful instead of challenging ourselves to overcome our fear and become the opposite? Brave, courageous?

I think about this question. A lot.

I believe it’s one of the most important questions we face today.

Let me me explain.

To start, we have to stop looking at things as if the truth is what is on the surface. We have to go deeper.

And yeah. It’s no secret that I am a fan of Jungian / depth psychology.

It’s part of being a writer, IMO.

As a writer, I study “story.”

And the more I try to figure out the relationship between character (who people are) and plot (how people behave, what choices they make) the more I understand this thing, “story,” as fundamental to what it means to be human.

It’s not just in books.

We all living out our own, personal stories.

Test this for yourself.

Think about a disagreement you’ve had with someone.

Now, instead of focusing exclusively on the surface “facts” of the disagreement, consider what it really means to you to be right — and what it really means to if you were wrong.

What I think you will discover, if you probe deeply and honestly enough, is that being right means that you are on the correct end of some scale that balances “good/right” against “evil/wrong.”

Winning arguments is always personal — always

Think carefully, as you reflect on that disagreement, about why you think you are “right.”

Perhaps you are “right” because you are a better observer of facts, versus your opponent, who failed to observe something. (Key words: “better observer.”)

Maybe you are better educated or have access to better information about an issue, whereas your opponent is ignorant or uninformed. (Key words: better educated, better information.)

In the case of some disagreements, maybe you have been graced with revealed information that is hidden to your benighted opponent. (Key words: graced vs. benighted.)

Regardless of the specifics, notice what all of these underlying assumptions have in common: “right” versus “wrong” in an argument is a value statement. And “value” within this context — a personal disagreement with another human being — is always personal.

In other words: it’s not about the argument.

It’s about who we are.

We are, each of us, “the good guy” in our own personal stories. (Psychopaths excluded obviously.)

Which brings us back to depth psychology.

When we are in the middle of a disagreement with someone, we think it’s all about what’s happening on the surface. We think it’s the material bits that are important.

But go down a level, and it’s about values, good v. evil.

“The science says this!” / “No, the science says that!”

“The facts are this!” / “No, the facts are that!”

“This expert is credible!” / “No, this other expert over here is who we should trust!”

And it’s about story.

When we argue with other people, we are actually defending not “a set of material facts” but the stories we believe about ourselves.

“On this issue, I am standing up for what is good/right. This makes me a good/right person.”

And that, my friends, is why arguments get so heated. We must win our arguments, because winning proves we are on the side of good.

And if we’re not on the side of good, we’re on the side of evil.

Me good, you bad

And we can’t bear the thought that we might be on the side of evil. We can’t bear the thought that if we were able to persuade some person or perhaps hundreds of millions of people to agree with us, it might do some great harm.

This is the real reason we so quickly resort to Ad Hominems when we disagree with someone.

We truly and instinctively need the person we disagree with to be inferior, in some way — because otherwise, we might have to face the fact that we are the ones who are inferior — literally “wrong” — literally taking the side of “wrong” or on the side of something “evil.”

So when we become frustrated that the person we’re arguing with won’t accept our points, we reach quickly for words that characterize our opponent as evil. Our opponent is stupid, a Nazi, a fool, etc.

Does this make sense?

Do you see how it is all story?

Which brings me to fear … and dragons.

It’s not just during arguments that we are in thrall to deeply emotionalized, non-rational currents of being.

It’s all the time.

You are the hero of your own story.

All the time, every day.

You are out there, every day, doing battle for good and against evil.

Many writers who study the craft are aware of “the hero’s journey.” It’s a concept popularized by Joseph Campbell in his book, The Hero With A Thousand Faces, where he identified and mapped archetypes that recur in our myths and folktales.

In The Writer’s Journey, Christopher Vogler proposed that writers can draw on these archetypes to add richness and depth to our modern stories. (And, by the way, my Character Tool for Novelists guided notebook includes space to brainstorm and document aspects of your characters’ archetypes and hero’s journeys.)

If you’re a writer, you should probably add Campbell’s and Vogler’s books to your library. (Note: the above are affiliate links, so if you click on them & purchase I’ll get a little money to help offset the cost of hosting this blog.)

But wait, there’s more!

This isn’t just about writing.

I believe that each of us, as human beings, would find it fruitful to think about how the hero’s journey relate to our lives.

And here’s the key:

To live the hero’s journey, it is critical to consider the meaning of “fear.”

So many people think that fear is a signal that we should run away, hide, avoid, seek protection.

That’s not what heroes do.

Heroes run toward the fearsome thing. They fight. They go to battle with it.

Now, look — since this is the interwebs, I suppose I have to state this flatly.

I’m not advocating that anyone should behave stupidly.

Heroes don’t rush willy-nilly at every dragon that pops up in their paths.

They also plan. They strategize. They consider how to best slay particular dragons before they sally forth.

You should, too.

Heroes gather allies. They gather tools.

You should, too.

But make no mistake: no matter how well you strategize, and gather allies, and gather tools, you will still be afraid.

In fact: that’s the whole point.

Fear is what makes it matter.

Hero’s journeys matter because of the stakes — and the stakes are always, always, extraordinarily high.

The stakes are death.

I opened this blog post with a question: what are we so afraid of?

It was a rhetorical question.

The answer is what it has always been: death.

Yeah, yeah, I know this can be nuanced. It’s not death, it’s the suffering that leads to death. It’s not death, it’s losing someone/something I love. Etc.

But as with everything else, below the surface, it is death. It is the end of something we want, whether that is life, or health, or well-being, or love.

The end = the death of.

And I’ll be frank, here: materialism has seeped into our psyches so completely and so insidiously that we have become, en masse, a little crazed about preserving our material selves.

If material life is all we have, why wouldn’t we value staying alive above everything else?

I have my thoughts on this topic — but that is for another blog post on another day.

For now, I’ll just say the following.

Dragons aren’t literally real.

But they do exist.

And one of their powers is that they weaken our hearts by frightening us.

We maybe can’t slay the dragons.

But we can strengthen our hearts.

So what are you going to do?

Are you going to be a hero?

And if not …

What is left?