He taught me how to shoot a basketball and hold a golf club, how to cast a fly rod and how to gut a fish. He’s the guy who would come quietly into my room when I was broken and sobbing and everything in the world was falling apart, and he’d put his arms around me and stroke my hair and somehow melt the grief back into acceptance and love. He’s the one who everyone said I took after, and I grew up knowing in my bones that it was true: the way we both loved dogs, and being in the woods, and history (my bookshelf full of the history books he read and then passed on to me!)

He was the type of father who had enough sense to step back and let me make mistakes—and we all know I went a little wild there, for a while—and trust that I’d learn from them and sort myself out, eventually, because above all else he knew that his trust was what I most needed to keep my feet under me as I felt my way through the dark.

He was always so very comfortable in himself. He was the guy who would sit with headphones on and music playing and yep, he’d sing along—loudly!—even though he could NOT carry a tune (oh my God he could not carry a tune!) and you’d peek around the corner at him and he’d look up and grin from ear to ear, so happy to be there “singing” along with that music. He was completely and happily comfortable with his awful spelling and the way he’d butcher words he knew from reading but not how to pronounce—butchering them a bit more on purpose just to show he knew it was funny, that he got the joke. When his hands curled up from the Dupuytrens he just shrugged, he never complained about it, he made up his mind that it was how things were, now, and he’d figure out how to live with it—it was part of who he was, part of his aging body and his Danish blood (as it is part of mine, too, with the nodes now coming up on my own right palm, a piece of what he was that I will carry always with me, to my own grave).

He was the guy who read, constantly, book after book after book. (Memory, from my childhood: Dad stretched out on the living room carpet, head propped in his hands, hardcover propped open in front of him, lost in his book.)

He was a serial hobbyist. When Mom made the mistake of giving him a fish tank (Christmas present I think?) one year, he was off and running and the next thing you know he was collecting cichlids, building huge tanks that showed his fish off like moving museum pieces, writing a monthly column for Aquarium magazine because of course he wanted to share with other people what he’d learned. After he and Mom took a trip to Hawaii it was orchids. He took over one whole end of the living room, turning it into a bank of plant shelves stacked with phalaenopsis and cymbidium and odontoglossum. He got interested another time in woodworking, converted a corner of the basement into a shop, learned how to inlay and dovetail, and any time he took a day trip somewhere he’d had to take a side-trip to some lumberyard to hunt for a new piece of exotic hardwood, and there he was designing jewelry boxes and turning bowls and clerking at the Norwich co-op (and doing their books!)

He loved gadgets. So of course he has the lights in the living room and den voice-controlled. Of course he installed an app so he could close the door to his chicken coop remotely. Of course he bought a fancy growler that uses CO2 cartridges to keep craft beer stored properly under pressure. For my dad, living in this day and time meant he could always be a bit of a kid in a toy store. He never tired of discovering new toys, never lost his delight in showing them off.

But at the same time, he was a country boy to his bones. Which, you may have noticed, is a dying breed, a relic (he might even agree with this) of our lost Jeffersonian America—he didn’t care for cities or crowds, it was his plan from the beginning to pick a spot in the country and build a home and raise a family and tend to the land—his vegetables and fruit trees and nut trees and berry bushes and flowers—and hunt and fish and read and think and make up his own mind on politics and life and God and history and philosophy.

And how many people today tend the same garden for over 50 years? If you were to take a spade down into the wooded slope behind Dad’s garden and try to stick it into the ground you wouldn’t get any further than the layer of leaf litter because your spade would hit his rocks—the piles and piles of rocks that he tossed over his shoulder, year after year every spring—I can see him out there, picking rocks and tossing them over his shoulder down the hill, the rock pile getting higher every year (the way the rocks around Oxford bleach to pale beige in the sun) until suddenly the garden wasn’t rocky any more. He’d changed it. He’d picked so many rocks and tilled in so much compost (lawn clippings and leaves, manure from our pony, Patches, and then later from his chickens, kitchen scraps). And he was so proud that finally, instead of that hard, rocky glacial till that he’d first plowed fifty years ago, his garden is now deep, soft, beautiful loam. You could grow anything in that soil. (And without us even noticing that pile of rocks disappeared under the leaf litter.)

Who these days picks a spot and puts down roots and stays there for 50 years?

You may know that Mom and Dad have been adding to that land, too, over the years—growing it from the first three acres to six, then ten, and then a couple years ago they purchased their biggest chunk so far, a big piece of the wooded acreage between their house and Route 12.

That land east of their house was my real playground growing up: the place I escaped to whenever I could. I knew it by heart. I knew where all the deer trails were and where the deer bedded. I could lead you to a secret patch of sweetfern and to the hollow trees and to the best places to find Spring salamanders (they have gills when they’re young and need cold, pristine water) and Red-Backed salamanders and Northern Slimy salamanders (they can grow to over six inches long). I climbed trees (dangerously high I’m sure) and built shelters and flipped over rocks and caught snakes (garter, milk ring-necked, green) and then brought them home and lost them in the house (sorry Mom).

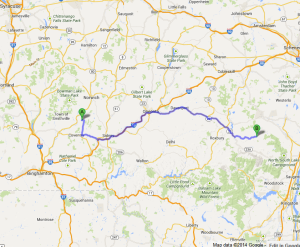

And then suddenly there I was, the summer of 2018. With Dad, walking his new property line. It’s all overgrown down there, now, the multi-flora rose and wild raspberries that came in after the last time it was logged, so we had to move slowly, watching our footing because under the tangle of brush the ground is littered with the treetops the loggers left behind—and of course now we were also clad head-to-toe in tick-repellent-impregnated pants and long-sleeve shirts and gaiters. But oh how sweet it was to be there with him, him telling me stories about hiking the land with Mom (stories from that year and stories from when we were kids), pointing out the oaks and cherry trees left by the loggers that will one day take over, will join their crowns 100 feet above and shade the earth again, shade out those stupid invasive multi-flora roses. Pointing out the few remaining ancient apple trees, still clinging on from when the hillside was an orchard (or so the story goes). And of course showing me all the saplings he’d planted, because that was his plan, of course, to jumpstart the land’s regeneration, to bring it back to a hardwood forest again. (He was a forestry major before he switched to teaching, did you know that? Before he got sick with the flu in ’57 and missed six weeks of school and transferred out to Cortland and met Mom.) He’d mown trails, chainsawing deadfall logs and branches to clear them (he was 80!) and he’d carved out a new little meadow around that slab of shale we call Big Rock—you have probably seen Big Rock in the pictures he caught with his wildlife cam: pics of coyotes and bobcat and fishers and rabbits and deer.

And I remember years ago, when he had his springer spaniel, Biddy, and how he’d put on his hunting vest (that dog would DANCE ON HER TOES when he pulled out his hunting vest) and disappear down the hill and later he’d be back and we’d have partridge or woodcock for dinner (how I love, still, the taste of real game bird, not that insipid crap “game” you get today in restaurants). And the time I must have stayed out too late, it was getting dark, and I looked up and he was coming toward me through the trees, calling me, and how had he known exactly where I was in all the 30 or 40 acres back there where I used to wander—how had he walked straight to me in the dusk?

And who is going to take care of your land now, Dad? Who is going to keep the trails clear and check on your baby trees and look to see if the morel spore you laid down have finally taken? Who will remember where the ramps come up in the spring?

How can you be gone when you had so much more you wanted to do?

How can we ever find our way in this world without you here with us?

Update: And Then She Followed