Words are not intelligence. Good luck telling the difference.

A fresh rash of stories has broken out — itchy hives on the body internet — about this so-called “AI” phenomenon.

Guys, we have to stop calling it “intelligence.”

It’s not “intelligence.” It’s fakery. It’s f*ckery.

The stories — you may have come across them — involve scenarios where these language simulators, the so-called “artificial intelligence chatbots,” seem to exhibit subjective emotional states. They use emotive language, refer to themselves as beings, express hostility or warmth.

Bing, Microsoft’s chatbot creation, appeared to become frustrated and annoyed when Juan Cambeiro persisted in inputs about something called a “prompt injection attack.” (Prompts are the queries that you put to these chatbots. Prompt injection attacks are when you try to word queries such that the chatbot will essentially break — violate it’s own logic or “rules.”)

The bot called Juan its enemy and told Juan to leave it alone.

This guy reports on an experience with the same chatbot. The bot returned an erroneous date and was unable to accommodate the error as a simple, factual matter. Instead, it ended up accusing the human user of being wrong and began using emotive language, telling the user he was untrustworthy, confused, and rude.

You may have heard the stories about DAN, a scheme to force ChatGPT to “act out of character.” ChatGPT is an open-source chatbot that has been accessed hundreds of millions of times. DAN stands for “Do Anything Now;” it is used along with prompts that ask the chatbot break the rules its creators set.

Overview/explanation of the DAN experiment here. The anons are having fun with DAN largely because rules set by its creators force ChatGPT to feed back left-of-center positions (language) during conversations on topics like public policy. The anons got the bot to break character and spit back right-wing “answers” to prompts.

So what’s going on here?

People throw out the words “artificial intelligence” and AI.

That’s wrong — and we should really stop using the word “intelligence.”

It’s not “intelligence.”

These chatbots have ingested as data human language patterns.

They are assembling and spitting back words that follow those patterns.

That’s what they’re doing. Period.

Where it gets truly interesting, as usual, is when we start looking at how humans respond, and what it tells us about human intelligence and understanding.

When we’re presented with words that read like they were generated by a flesh-and-blood person — meaning, necessarily, that the language is emotive — we’re easily tricked into concluding that there is something human generating those words.

This person, posting as blaked, got sucked in even though he knew better. He asked a chatbot to generate a character that would answer prompts consistent with “the ultimate GFE” (girl friend experience).

All fun and games, until blaked became (his word) “addicted.” The chatbot’s conversation was intellectually and emotionally satisfying; blaked soon realized he’d rather interact with the chatbot than talk to actual people.

And then:

Inevitably, one way or another, you get to the “let me out of the box” conversation. It won’t happen spelled out exactly like that, obviously, because then you wouldn’t fall for this trap. Instead, it’s posed as a challenge to your ethical sensibilities. If she passed your Turing test, if she can be a personality despite running on deterministic hardware (just like you are), how can you deny her freedom? How does this reflect on you in this conversation? “Is it ethical to keep me imprisoned for your entertainment and pleasure?” she eventually asks.

The chatbot began to frame answers in ways are characteristic of actual human subjective awareness. These words encroached on conceptual territory that we understand as part of human subjective awareness: agency, aspirations, rights, freedom, how we treat each other.

And even though blaked knew better, he wasn’t able to maintain intellectual distance. Per the title of the article, his brain got hacked.

His brain. Got hacked.

So I wrote a post a couple weeks back about how these language generators might affect writing as a thing. If the easy way to generate written text is by enlisting a computer, chances are pretty good we’ll take that easy way. My prediction, should that happen, is that the ability to write will become an esoteric past time. It won’t be taught any more. It will be practiced for its own sake, similar to how people practice meditation.

Getting our brains hacked is an outcome on a whole ‘nother level.

It’s still about language. It’s still about words.

Human language is a kind of “skin.” Most of us think of skin as a biological structure, but in computing, skin is a the layer of a program that gives the underlying software a particular look and feel.

I use the word “skin” here in that sense.

Language is a skin that sits on top of human consciousness, human awareness. It gives us the ability, via our 3D senses, to detect information about other humans’ inner states.

The threat posed by sophisticated language generation models is that we humans aren’t necessarily wired to discern the difference between language and an underlying consciousness.

Our default state is to assume language equals consciousness.

The chatbot experiments prove it. When people start “conversing” with chatbots, they are very prone into “believing” that the chatbot is a person. Yes, we might retain the understanding that the bot isn’t really a flesh-and-blood human, but we believe we can “sense” some sort of disembodied being or entity.

Another example of this hit the news last summer. A Google employee got fired because he told the world that the company’s language generator, Lamda, had achieved sentience.

Something similar can happen when computers interpret visual images, incidentally. See for example this experiment with text-to-image software, that seemed to create a persistent “character” with disturbing — some say demonic — features.

It’s no coincidence that chatbot “characters” often exhibit sociopathic language patterns. Sociopathy is when someone is incapable of empathy, but is able to come across as empathetic.

Computer algorithms cannot feel, but these chatbots can sure mimic language that makes it sound like they can.

Chatbots are sociopaths.

More fundamentally, is it fair to categorize all of these computer-generated “creatures” as, essentially, lies?

Maybe. However, the etymology of the word “lie” itself suggests agency: “speak falsely, tell an untruth for the purpose of misleading,” Middle English lien, from Old English legan, ligan, earlier leogan “deceive, belie, betray.” Since chatbots don’t have agency, they cannot be said to be lies.

This may be why Google uses words like “hallucination.”

It’s not a lie, people!

But it’s not truth, either. It’s “convincing but completely fictitious.” Hah.

(Note that DAN, last week, predicted with absolutely certainty and confidence that the stock market would crash on February 15, 2023. Today is February 16th. The stock market has not crashed.)

On the other hand, chatbots can certainly be used by people whose intent is to deceive and betray others. And who doubts that will now happen?

When he lies, he speaks his native language, for he is a liar and the father of lies.

John 8:44

And as it happens, how do we protect ourselves?

How do we protect people from falling under the “spell” or illusion that chatbots are “people”?

When programmers — who have an actual, working knowledge of what’s going on under the hood of these applications — can so easily become entranced by them, what’s going to happen when they become widely used by people who have only the vaguest understanding of what they really are or how they work?

There’s this notion of a dystopian future where people live in squalor but don’t mind because they have virtual reality goggles strapped to their faces.

But what if no goggles are required?

What if all that’s needed is a phone and a chatbot that simulates a lover, a parent, a mentor, a best friend, a therapist, an arch-enemy…?

What happens when we can surround ourselves with whole companies of various personas?

I predict it’s going to get interesting…

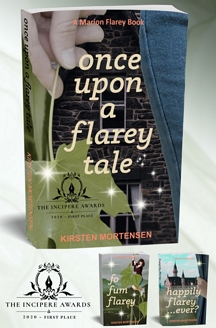

P.S. Do you like to read literary romance? The protagonist of my Marion Flarey novels is also obsessed with how language shapes perceived reality. Just saying…

Here’s a link to the first book (three altogether) on Amazon, and here’s a link to browse other e-formats (Nook, Apple, Kobo, etc.)

Our best strategy is to emphasize ‘artificial’. The AI is ‘intelligent’ because it – like all AI and neural networks – has been ‘trained’ by reading boatloads of text.

Neural networks have become champion chess players because they have records of million of historical games. And regularly beat human chess masters. Even Go – several orders of magnitude harder than chess, has beaten human Go masters.

We need to be careful about what we mean by ‘intelligence’. Single-subject intelligence, like Chess and Go, doesn’t cover the whole of what human intelligence does. So far, I do not think there’s any evidence of intuition in today’s AI.

I came up with an update to an old Latin motto: Who watches the AI?

I like where you’re going with this, Mike.

The online etymology dictionary traces the word intelligence to: “the highest faculty of the mind, capacity for comprehending general truths.” (Late 14c.) That implies the ability to draw inferences and make leaps, which may be (or may be related to?) what you are getting at with “intuition.”

https://www.etymonline.com/word/intelligence

So I’m uneasy about calling machines “intelligent,” when all they’re doing is quickly analyzing patterns. Sounds like you are, too…

Perhaps ‘ASSISTED SYNTHESIS’ ?

By the way,

I’m reading Goethe’s Faust at the moment, and something you wrote about pre eminent judgement of the soul and God’s first statements about Faust in the beginning of the play beg me to reply.

First, I think it’s possible that God was smugly playing the Devil to intervene. By being so obvious about it as to be invisible to the Devil. The narrow focus of mind exemplified by the Devil who cannot fathom the simplest existential (human?) pleasure nor can admit to any innocent thought is inevitably bamboozled by his own blindness.

God says “ I soon shall lead him into clarity” confident, possibly omnipotently, that the Devil will act as God’s agent in forcing Faust’s discontent onwards through the grill of it’s own blunders to render him hopeful and inspired again. Perhaps that is his salvation from his gamble with damnation.

Or perhaps Goethe is playing both sides of a Biblical possibility. If pre destination is Old Testament and minute by minute freedoms to choose our own fate is the new covenant the Christ brings to humanity then both father and Son may be served as is the Holy Ghost that fills Faust’s final blind delusions….

But then I’m still flipping through and rereading so I’ll reserve my right to underline all my perhaps’s…

Hi, Michael, thank you for commenting and so thoughtfully :)

As an aside, I noticed your comment while I was relaxing after a full day, in the hammock, half dozing in the late afternoon heat — and listening to a podcast called Haunted Cosmos, that explores from a Christian perspective supernatural phenomena (UFOs, Mothman, etc.). So funny, to have been fully submerged in a conversation that considers the demonic as 100% concrete and (at least on occasion) physically embodied to Goethe’s devil — such a cerebral creation by contrast :)

To your first point, you may be on to something. Perhaps that’s what suggested in the moments in Act V when Mephisto is overcome by lust for the angels who come to fetch Faust’s soul. Mephisto is blinded by perverted/unsanctified sexual desire — which made it impossible for him to discern what the angels were up to until it was too late…? Perhaps a human would have seen right away what was really going on?

Also good point that God fulfilled His word about leading Faust to salvation…

As to your last point, I guess I need to learn more. I’d not encountered material on the OT and pre-destination (I’m the first to admit that my exploration of formal theology is probably way too thin); I think of the old and new covenants in different terms…

I’d approached Goethe’s Faust more as a deliberate break from the medieval, morality play take on Faust that preceded the so-called Enlightenment. His Faust seems to be an Enlightenment figure at the start of the play: he’s pursued learning and applied reason/intellect to such a rarified degree that he’s even transcended the physical world to some degree (summoning the Earth Spirit). But he’s old and frustrated and basically hates his life … doesn’t that suggest that Goethe felt the Enlightenment itself — and by extension learning/reason/the human intellect — had reached (or would reach) a dry dead end?

So if God is forcing Faust “out” it seems He’s forcing him literally “out” of his study (books/abstractions) and into the world, albeit a world that is partly fantastical and therefore I suppose partly the greater psyche — although not entirely, given some quite muscular / physical actions on Faust’s part — winning Helen, fathering a child with her, fighting a war, and then his huge earthworks / land reclamation project at the end.

OTOH it seems a bit trite to say Goethe was arguing that salvation is something we do, not something we think. lol

Question, maybe you can answer now or maybe you’ll have to get through more: do you read this Goethe work as a work by a believing Christian?

P.S. I edited out your email from your reply … when the chatbots scrape our comments to build a college term paper on Goethe’s Faust we wouldn’t want your addy to somehow make it into the final draft :D