If there’s no one beside you

Death Cab for Cutie

When your soul embarks

Then I’ll follow you into the dark

Last year was an awful year.

I know, I know: it was an awful year for many of us. Most of us, perhaps. And I am old to enough to know, in my bones, that the man on the screen spoke truth when he said that our personal problems don’t amount to a hill of beans.

They don’t. They really don’t.

But it was a year to me personally, of awful grief: first, my father taken down by Covid in April 2020, and then less than 10 months later, my mother — the woman he loved so much, that he cared for so well — their wedding photo was his Facebook avatar — followed him.

Which wasn’t entirely a surprise. They were married just shy of 60 years. She was already, increasingly, frail (the more frail of the two of them, by a lot, or so it seemed until he got sick); her mind — her memory — was failing her. She was very dependent on him. How it must have terrified her, when he was suddenly gone…

We know these things often happen when two people are married for 60 years and one of them passes.

What we can’t know, until it happens, is the manner of it — the manner of the passing — the suffering. The insanity of the living that surrounds the suffering.

In any case, her time came, and it was over.

She passed in January.

I haven’t been able to bring myself to post about it.

It was a year when so much that I hold dear has been lost. It hurt, terribly. It still hurts. I can’t imagine that it will ever stop hurting.

But I’m not alone, I know. Nothing that has happened to me — to our little family — has not happened already to countless other souls.

And Mom — I’m going to speak these words to you, Mom — as you were dying, I began asking myself. Now that so much of what I held dear is lost, what is left?

And I realized that what I remember from my earliest, earliest childhood is only six things.

Six, really simple things.

You. I remember you, Mom.

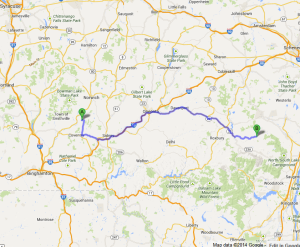

And five other things. Dad. Sigrid. Beautiful Oxford, New York. Nature. And God.

And what else I also remembered, finally, in these past few weeks, is that it was you, Mom, who brought me God.

And not as mere ritual. Not as just church on Sundays and grace before dinner and prayers at bedtime, but as a way of being in the world – a cultivated habit of constantly turning inward and talking to God, asking questions of God. Expecting of myself that which God would expect: to live authentically, to be unafraid of even painful decisions, to be unafraid of even suffering – because being right with God is always what is most important.

I turned 60 last March. Fifty nine years with Dad. Fifty nine years with you, Mom. And then, in the span of a few short months, you both passed through that one-way door, and were gone.

And every one of us, if we live long enough, will lose our parents, and know what it is like to lose our parents. It is a shock. A systemic shock.

In his book Hauntings, psychologist James Hollis observes that to lose your parents is to lose your home. That resonates with me. It’s why losing you and Dad felt like the ground was being yanked out from under me.

Losing our parents turns us into wandering souls. And then we have two choices. We either wander, lost, in what’s left of our old world, or we try to find our footing in a different world, where home isn’t a place and it isn’t a person; where families can be destroyed in an eyeblink — where home is defined by our relationship to the infinite itself — with something that can’t be touched or tasted or seen.

Losing Dad was a shock that brought me to my knees . Losing you, Mom, was a bitterly hard aftershock. But also, in a strange way, it cast me back to what you taught me.

There is nothing in this world that does not change. We have nothing in this world to hold onto.

Instead, we have to hold onto God, even when God doesn’t show His face, even when our faith, like the knight said in the Bergman film Seventh Seal, “is like loving someone who is out there in the darkness but never appears, no matter how loudly you call.” Even when, as the Book itself says, everything we puny humans wish to have or be or fight for is really nothing more than striving after wind.

Mom, you taught me that it is the calling that matters, not the answer, because it’s the calling that is our true home.

I confess. I didn’t fully appreciate your gift — the enormity of your beautiful gift to me — until you were dying. Until I knew we were going to lose you.

I did have a chance, thank God, to tell you, before you left, that I finally realized this gift. I got to tell you how grateful I am to you. That the gift you gave me is the most precious thing I own.

I love you so much, Mom.

Thank you so much, Mom.