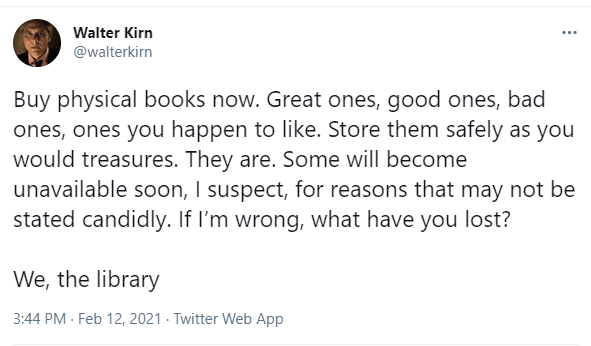

I came across this tweet around the time Kirn (substack here) posted it, and it continues to haunt me.

I don’t know how many physical books I have collected. Five or six hundred, perhaps. It seems, to me, to be “not a lot,” so it shocked me just now when I quickly estimated the count.

If they were shelved compactly in one place, they might cover one wall or so of a smallish room. And yet. They take up space and gather dust. And every time I move (I have moved, on average, every 3.5 years since I graduated college — does it ever end, this moving?) they are such a troublesome thing to pack and unpack and sort and re-shelve.

So when my sweet father, who read books constantly, gave me a Kindle (I’d begged him not to, but he loved his so much, and so much liked to share that kind of thing with his family) I thought, okay, now I’ll be able to read on without piling up more and more physical books. This is good, I thought. “I’m comfortable that certain experiences are supposed to be ephemeral,” I blogged. “I’m okay with some books as experiences rather than things.”

But then came the stories about Amazon erasing peoples’ books from their Kindles (some sort of issue with copyright or publisher disputes, the story would go) and I became a bit uneasy.

When you buy a “book” for an e-reader, you don’t really own the book, as it turns out. You have paid for permission to read something that belongs to someone else. And “they” can take back that permission any time they please. (And my father’s Kindle? The books on my father’s Kindle? I took photos of the screen — screens, pages of them — so that I would know what books he “owned.” They are gone, now that he’s passed and no longer “pays” for his “account.” There’s your “ephemeral.”)

I have also had a longtime habit of picking up used books that struck me as unusual, or that I learned would be going out of print. I bought an old edition of The Joy of Cooking when I learned that new editions have dropped the recipes for cooking game. I read at some point years ago that Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations was being revised — modernized — so I hunted down a second-hand copy (the centennial edition published in 1955). (I adore that book. It may be my take-on-a-desert-island-game book.)

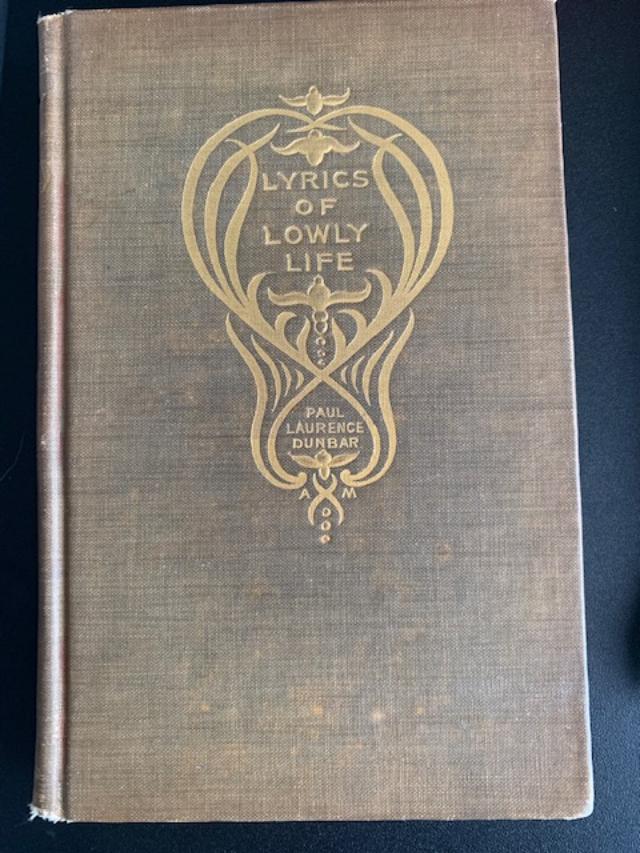

I’m old enough to have lived through the transition as second-hand booksellers began selling online. It drove up the price of old books — that copy of Lyrics of a Lowly Life by Paul Laurence Dunbar that I picked up for 50 cents in a junk store in my home town in the early ’80s would be displayed in a locked case, today, and likely priced at $100 or more. (Of course you can buy reprints of it for pennies — have you ever bought a book, thinking it was second-hand, only to find out it was a cheaply made reproduction? The quality so poor it was basically unreadable? I have. I will not, ever again, if I can help it.)

And I remember as well reading — also years ago — that decorators were buying up antique hardcover books — the ones with ornately decorated covers and gilt-edges pages — and using them as, well, decorations. In some cases they were gutting the books and using just the covers. Because what mattered wasn’t the words inside but the effect walls of books would convey, the image they’d convey of erudition.

It was around this time that I became weary of being outraged. Is that cynicism?

Not to say that I’m no longer outraged, ever. I am, believe me.

But — and this is more pronounced now than ever, since I lost both of my parents (within a span of less than a year), my birth family now basically as gutted as a home decorator’s empty books, not to mention these godawful exhausting never-ending lockdowns — I am, more and more, handling my outrage by becoming quiet, by turning inward. I am thinking — all the time, basically — about soul, and about words, and about preservation. Not preservation of myself but of what really matters — what will always matter.

Thinking about whether the outward things I preserve, the words I preserve, could ever help someone else, one day, grope a bit closer to some faint Light.

That I shouldn’t gamble with such a thing.

It’s been several years, now, since I began to regard my Kindle as a device, solely, for what I consider to be throwaway books — I know that sounds pejorative but what I mean is books I would under any circumstances read only once and then pass along (and the Kindle is also very good for reading samples for free).

I’ve started to buy up physical copies of the books on my Kindle that I do not consider one-time reads.

Which leads, of course, into the next phase of my weird relationship with Amazon. (Seems it’s always about Amazon, isn’t it?) Now with their new policies, their decision to start taking books off their platform — once again reminding me as it does all writers of our uneasy truce with That Company: I am utterly dependent on Amazon if I’m ever to sell my novels in any numbers whatever; “my” readers are not really “mine,” they are Amazon’s “customers,” no matter how ridiculous and unfair that may be (and before you defend them — because yes, I know they do me a service by building their platform and attracting traffic and letting me sell my books there — when I have, in the past, bought other things from them, cosmetics or whatever, I have gotten emails from the seller, I have gotten direct mail, snail male from the seller. How can other vendors “own” customers that came to them via Amazon but writers cannot? There is no happy answer to this, I suppose. I suppose these other sellers have done their own fulfillment. I suppose there are so many writers that we are, to Amazon, something of an unwashed hoard, with a handful of exceptions more trouble than we’re worth.)

In any event, I’ve been going to Alibris instead of Amazon more and more. Telling myself maybe that helps, in some small way, other booksellers (“hello?” “echo echo echo…”). And I am picking up more and more second-hand copies of old books. Despite the fact that my shelves are full and we’ll likely be moving again sometime in the not-too-distant future and once again I’ll be packing books in boxes…

And I am increasingly aware of how I feel, when I sit near my shelves of books, thinking or journaling or writing, and I need to look something up and I scan my titles and find a book and page through it. Like right now, for example. Marshall McLuhan, The Global Village (I own the Oxford University Press 1989 edition):

All media are a reconstruction, a model of some biologic capability speeded up beyond the human ability to perform: the wheel is an extension of the foot, the book is an extension of the eye, clothing an extension of the skin, and electronic circuitry is an extension of the central nervous system…

My books — I feel this as I sit near them, scan their titles — are also an extension of my mind, of my memory. I very often go back to books I read decades ago (I haven’t opened the McLuhan in probably 20 years) with that same felt sense that arises when we go back into our mind’s memory banks to pull something out that we once experienced and would like to look at it again and draw upon, again, because it will add some sort of richness or meaning to what is happening now, today.

So if I look for a title and can’t find it right away (I don’t have enough space on my shelves; about half of my books are stacked behind the other half; my books hide on me, sometimes) I become anxious, even, at times, agitated. It’s like I’ve lost a bit of what should be there, should be recallable. (I was looking the other day, for my copy of The Great Gatsby and can’t find it and it still bothers me…did I lend it to someone? Should I buy another copy? Would I be able to find the same edition I owned?)

Ephemeral, indeed.

Sigh.

Buy physical books now. Great ones, good ones, bad ones, ones you happen to like. Store them safely as you would treasures. They are. Some will become unavailable soon, I suspect, for reasons that may not be stated candidly. If I’m wrong, what have you lost?

We, the library.

—Walter Kirn

Books as an extension of mind — an extension of our thoughts and memories. Individually and collectively.

“We, the library.”

What happens to our books, if we, their contemporary guardians, decide to begin culling them?

And if we cull them, what injury are we committing that we cannot feel (the brain can’t feel pain, right?) but that will one day exact an awful price — one day we’ll wake up and sense a gaping hole where, we know, some memory ought to be?

I am buying more books, now, than I’ve bought since I was in college. Unapologetically. Knowing that it means I have more “stuff” that I will need to cart around, that someone will one day have to dispose us when I am dead.

Unapologetically.